I hate impending doom.

Back in September’s “Allen Hates Politics, Part 2.5,” I talked openly about my seasonal mood swings: “Wednesday was officially the first day of autumn and also the first day where the weather didn’t remind me of impending climate change. Cool weather means a lot of things for me. It means I can finally sing Christmas songs, unplug the fan that has been working overtime to keep me cool in my room and go outside with a sweatshirt… it’s not so sticky and I’m feeling optimistic about life.”

Well, that wondrous moment came and went about as fast as it could. Five weeks later and it’s just cold and rainy and I’m stuck inside my room or at school doing some mundane task while trying to find new music for my playlists. You may have caught on by now, but my mood hasn’t exactly been bright and sunny; case in point being that I wrote a 2100 word column about nuclear war last week. Because of this unending cloudiness, my feelings of impending climate doom have reemerged, making me quite literally “under the weather.” I suppose this is what I get for living in the Midwest.

Impending doom is a hard feeling to describe but a pretty widespread affliction among younger generations. I’ve dealt with my own instances of impending doom throughout high school: standardized tests, national-qualifying debate competitions, Panorama deadlines and even allergic reactions (anaphylaxis is said to bring impending doom and I can confirm this). And even now I’m trying to avoid thinking about college apps, in which I’m on a direct collision course with, only steadied by an increasingly false conviction of “I’ve got time.”

“I’ve got time” is only one of the ways I lie to myself to maintain a thinning mental balance that allows me to be content with my life. And it works fine in most instances, you know, except for when it doesn’t. But still I’m able to pacify my impending doom into a simple stress or complaint, mitigating its scarring effects. Impending doom, for me, stems from a deep uncertainty about my brittle future. We anticipate that some kind of pain is arriving but we are unable to change its trajectory. We pray that it never happens, but we know those prayers are futile.

And when I said it was widespread among younger people, I meant it. It’s in a phenomenon called “eco-anxiety,” an impending doom regarding our warming blue marble. As we reach higher and higher degrees of warming and as young people become more and more aware of their crumbling futures, we become increasingly mentally strained to a point of exhaustion or depression.

Somewhat famous environmental activist Greta Thunberg recently produced a video with the New York Times regarding the depressingly little amount of progress we’ve made on climate change, highlighting and validating our feelings of eco-anxiety. We aren’t crazy, we aren’t stupid and we definitely aren’t wrong. Global warming is coming. No, it’s already here. And it’s going to wreak havoc on our lives.

Now it’s a matter of how much.

Global scientists cite 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming as the threshold for avoiding catastrophe. Pessimistic estimates show that 1.5 degrees of warming is inevitable and we’re bound for more unless every single nation starts decarbonizing right this second.

Now I’m going to count to three. One… two… three. Let me check the news again. Nope, nothing. Oh wait, let me check again. Yup, nothing again. Every second that passes, we are just that much closer to catastrophic amounts of warming. Seconds turn to minutes, then days, weeks and months. That Vox article was published nearly two years ago and we have hardly budged since then.

Climate change is right in our face. It’s not subtle. Scientists have waved it above our heads for decades and counting, and yet humanity closes its eyes, covers its ears and says “LA LA LA” until it doesn’t bother us anymore. It irks me that we aren’t anywhere near solving the guaranteed apocalypse we’re bound to face.

I say “pessimistic” estimates, but what I really mean is “blunt.” These predictions unveil the most about our climate crisis. It tells us the truth as it is: that limiting warming to 1.5 degrees is virtually impossible. We should’ve started 20 years ago, or maybe 10 years ago, or last year, or last month or yesterday. Yes, we shouldn’t have had to wait until now to do something.

But as a teacher once told me regarding late work, “The next best time to do it is now.”

Optimism’s Flaws

A lot of people criticize “blunt” estimates for being overly dramatic and depressing to a point of inaction. They say that telling people that efforts to prevent 1.5 degrees are futile only turns people away from this global movement and collapses climate action. This is a school of thought I like to call the “anti-doomer” group. These doomsday naysayers profess an unlimited amount of optimism for our global efforts to prevent 1.5 degrees. Not only that, but anyone who doubts their optimism is automatically relegated to “doomer” status – climate nihilists who only sit idle as the human race crumbles right before their eyes.

It’s becoming increasingly difficult to be an anti-doomer. Mostly because many anti-doomers, keeping up with their research, understand more and more the viewpoint of the people they antagonize. The general sentiment for a long time was, “We have everything we need besides the motivation.” The new growing sentiment is, “We have lacked motivation for too long and we’re paying the price for it.”

Because ultimately, being anti-doomer is a hopeful excuse for avoiding a difficult reality. That reality being that climate change is going to make life awful. For all of us. And the longer anti-doomers hold on, the more abrasive the cognitive dissonance becomes.

In my opinion, the faster you come to terms with this idea that we’re kind of screwed, the more you’ll end up cherishing the incredibly beautiful, yet fragile planet that we are lucky to live on. And in order to continue cherishing the current Earth, we ought to do the most to preserve it while we can.

Pessimism’s Flaws

There are two other schools of climate thought we have to talk about. The first one I’ll call the “colonizers.” This group seems to take a little too much inspiration from Christopher Nolan’s “Interstellar.” Or maybe they’re inspired by “Wall-E?” The premise behind both movies is that when a climate disaster strikes Earth, humanity hops on a spaceship and inhabits a different planet. And colonizers really take that to heart. When your house burns down, you know, you can just move into a new one. But the colonizer theory doesn’t stop there.

Once we reach other celestial bodies, the colonizers branch off into different trajectories. On the more extreme side are the people who don’t understand space travel, saying that we can just shove all 8 billion of us into spaceships all Chris Pratt and Jennifer Lawrence “Passenger” style and just inhabit a nice little exoplanet a couple dozen lightyears away. I don’t think I need to say anything about this.

On the more logical (with a grain of salt) side, some colonizers say we can 1) place humans on other planets so that they can 2) mine stuff and bring it back to Earth for the rest of us to enjoy! Ah, so they predict that transporting 8 billion people isn’t feasible and find a nice workaround: since we’re only mining and polluting on another planet, Earth will no longer be dirtied by humanity! And because we stopped polluting on Earth, no more climate change.

Phew, crisis averted! Why didn’t I think of that before? Ugh, I love you, Elon Musk!

Besides the fact that it will take us another couple decades to set foot on another planet, not to mention the impossibly hard task of mining and then bringing back massive amounts of extracted resources from other planets, space exploration will take lots of fuel and production that only accelerate our climate crisis. There are no “eco-friendly” rockets. Space exploration is too slow, ineffective and inefficient. In other words, we will all be dead by the time our interstellar moguls find a way to inhabit a new Earth-like body.

Space colonization is a very extreme form of pessimism that highlights a certain irresponsibility of our human race – that Earth is expendable in some way or another and that any self-preserving act can be morally justified under some human-based, or anthropocentric, calculus. Everything else can wither as long as we live and that’s okay.

Eco-nihilism, if it can be called a pessimistic view, is a more concrete perspective.

Typical depictions of nihilism usually are something along the lines of “life is meaningless so I think I will just die or be useless now lolz,” which is a pretty inaccurate take, yet sort of in the right direction of the nihilist viewpoint.

They might as well be right about life’s supposed “meaninglessness,” but it’s not really “meaningless” as in “life is devoid of meaning,” instead it’s more like “meaningless” as in “my life is so minuscule in comparison to everything else that it hardly matters.”

“There exists, to use Henry Sidgwick’s influential phrase, the ‘point of view of the universe,’ that is, the standpoint that considers a human being’s life in relation to all times and all places. When one takes up this most external standpoint and views one’s puny impact on the world, little of one’s life appears to matter,” according to Plato’s Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

And in the case of eco-nihilism, it’s a sense of species-wide minuscularity: that our population of bipedal ape descendants could go away and it would not only matter little, but also bring justice for the crimes we’ve committed against all other life forms on Earth.

Thus, the solution. Die. It’s not very pleasant, admittedly, but it definitely raises good questions about human existence. Think, for a second, about a world without humanity. What good have we done for the planet? What even can be considered “good?”

Eco-nihilists, although on the wrong side of thought, in my opinion, challenge us to think about humanity differently – the “point of view of the universe.” They challenge us, even for a second, to imagine something entirely external to humanity. And that is a mind-bending second to experience.

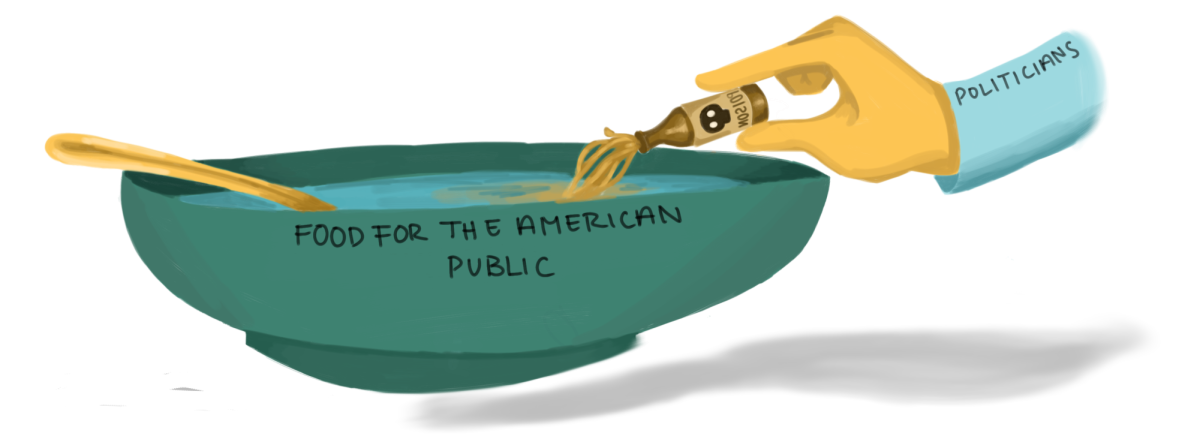

But yeah, it’s still stupid. For one, who deserves to die from climate change? Is all of humanity to blame for a climate disaster? A resounding no. Don’t be fooled into thinking that all of us are bad for the environment. Most of us aren’t at all to blame for warming. It’s sad, but generations of us are born into a system that compels us to consume products made from fossil fuels and think nothing of it. Those who are driving us into a wall aren’t the general population, but instead those at the top who insist on continuous pollution for their benefit and most importantly, their profit.

Eco-nihilism assumes some shared responsibility as a species for global warming. But that’s just not the case. Charging your phone is incomparable to the mass amounts of pollution that go into coal, oil and gas extraction. We may share some responsibility, but it’s certainly not proportional or uniform at all. And yet the punishment, death, is proportional, uniform. Death affects everyone the same, but we all deserve death disproportionately. Why should I receive such a sentence for a crime I was not involved in?

Doomer Thoughts?

Even when the blame is fairly delegated, at the end of the day we’re still headed towards climate catastrophe. The impending doom of climate change is only worsened by acknowledging the uneven blame. We become aware that the people who are most at fault are the same people who have the most control of the survival of our species. We really put the fate of our species in the hands of the people who have the most to gain from polluting. “My disappointment is immeasurable and my day is ruined,” I’ve once heard.

Impending doom is a hard feeling to describe. I feel powerless. I feel desperate. I feel futile. And yet, because it’s humanity, I feel somewhat hopeful. In the face of futility, I feel even the smallest chance of hope for our situation. That someone will answer my call, because that’s just what I want to believe. But it’s difficult to keep holding out, like two equal sides of a cognitive tug-of-war slowly tearing apart the rope on which they pull from. To ease my tension, I’ve come to a compromising answer.

Optimism is sometimes misleading. Pessimism is sometimes paralyzing. How we are to view climate change is entirely personal, even though it is such a global phenomenon. But to deny that we should at least try to live in greater harmony with the natural world, that we should at least try to protect our planet, is to deny the possibility for all of posterity to experience the happiness and beauty that is left of the little blue marble we call home. Failing or succeeding is irrelevant, as long as we are compelled to trying something, anything that preserves Earth’s beauty. It becomes not what we can do for humanity or justice, but what, in our present condition, we can do for Earth itself, regardless of our past mistakes. That in and of itself gives me the strength to wake up every morning and live out these cloudy days.

In conclusion, I hate politics.