I hate Facebook.

What even happens on Facebook? Every time Facebook makes headlines it’s either silly or downright horrendous. Sometimes it’s just Mark Zuckerberg unveiling some random product. Other times it’s the Facebook algorithm becoming a breeding ground for white nationalists. The contrast between each new development baffles me.

In recent years, Facebook has gotten into scandal after scandal, each instance revealing a portion of the Facebook underbelly. What was once just a website for rating Harvard students’ attractiveness became an American tech conglomerate in charge of multiple widely used apps and platforms: Facebook, Instagram, Messenger, Whatsapp and so much more. So. Much. More. Thus, Facebook’s domain now hosts billions upon billions of users, posts, comments and interactions.

To mediate the sheer number of happenings on these platforms is no small feat, I’ll admit. But, as Uncle Ben once said, “With great power comes great responsibility.” So is Facebook to blame for some of the terrible things that happen on their platforms? Or are the users at fault?

Frances Haugen, a former Facebook product manager, blew the whistle and said Facebook is the culprit behind several core issues in their domain. Anorexia among Instagram’s young women, ethnic violence in places like Myanmar and Ethiopia, the Jan. 6 insurrection and mental health were all on the table at Haugen’s congressional testimony.

But this story started quite a while ago. Let’s catch up.

The Wall Street Journal first shone a light on these issues about a month ago with the release of the Facebook Files, an investigation of Facebook’s own internal documents that Facebook kept from the public. It was later revealed on 60 Minutes by Haugen herself that she leaked the files. That episode would thrust her into the spotlight as she discussed her time at Facebook and her issues with the company.

This all led up to her congressional testimony on Oct. 5, where she hammered Facebook for putting their profit margins above their users. Although she was critical of their management, Haugen expressed optimism for Facebook’s potential as a force for good.

Haugen did specifically say that her intention was never to get people to hate Facebook. But I’m going to diss them anyway because there is a much longer, much more repetitive history behind Facebook scandals that’s become hard to ignore. To examine this is to get to the bottom of the question: what relationship should tech companies have with their users?

Last time Facebook made news this big, it was the 2018 Cambridge Analytica scandal. Basically, Trump’s 2016 campaign team hired Cambridge Analytica to collect data on millions of Facebook users to identify personalities and influence behavior regarding the election. Users consent, when making an account, to their data being collected for academic research, but this was definitely not the type of project that users consented to when signing up for Facebook.

This massive data leak, compounded with accusations of Russian interference and fake news dissemination, put Zuckerberg and Facebook in a bit of a conundrum. Zuckerberg infamously testified in front of Congress, sparking debate about privacy on social media. Again, the theme seemed to be that Facebook put its profits over their users, echoed by Sen. Mark Rosenthal, “Unless there’s a law, their business model is going to continue to maximize profit over privacy.”

The irony of the Analytica scandal was that it proved to be a win for Facebook. Its stock jumped 4.5% following the testimony and Facebook owed just about nothing to the government besides a few apologies.

And this isn’t his first apology. Not even close. Zuckerberg has been there and done that for 14 years straight before the hearing even began, according to Wired’s Zeynep Tufekci. Facebook seemingly apologizes, shrugs and gets away with it every time.

So while Haugen claims her optimism for Facebook as a company, I’ll take a more pessimistic stance on it all. Based on Facebook’s history, nothing will happen to them. But something should happen to them.

To start, we can talk about the platforms themselves. Social media algorithms absolutely suck. The primary issue with these algorithms is that they encourage and balloon preferences in order to increase an app’s use and engagement. For example, I tend to watch a lot of basketball clips on Instagram. Instagram’s algorithm, recognizing this tendency, intermingles random kids snatching ankles and sports analyst clips with my usual NBA highlights to try to get me to stay on the app.

The problem arises when a person watches clips of Tucker Carlson, a popular Fox News personality, and sparks a rather harmful chain reaction. The algorithm recognizes this Carlson tendency and slowly, but surely continuously feeds the user more and more Tucker Carlson and Carlson-adjacent material, eventually leading them to be Great Replacement sympathizers. Facebook, with its many platforms, amplifies certain preferences to a dangerous tipping point.

Same can be said with mental health and anorexia: teens see skinny people, ideal lifestyles and “self-help” videos and slowly deteriorate mentally and physically as they continue to consume media and adjust their lives to fit whatever idea that media encourages.

Facebook knew what was going on. They did their own research to demonstrate all of these possibilities that I just mentioned were very much real. And then they scrapped it and turned a blind eye to it all to preserve their own interests.

“This isn’t a community; this is a regime of one-sided, highly profitable surveillance, carried out on a scale that has made Facebook one of the largest companies in the world by market capitalization,” Tufekci wrote. “It ought to be plain to them, and to everyone, that Facebook’s 2 billion-plus users are surveilled and profiled, that their attention is then sold to advertisers and, it seems, practically anyone else who will pay Facebook—including unsavory dictators like the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte. That is Facebook’s business model.”

It would be easy to denounce Facebook for their misconduct and just say, “do better.” But what we need to realize is that this isn’t an irregularity of Facebook’s business model. This isn’t just a hiccup, but rather a symptom of Facebook’s ill practice. Facebook is supposed to work this way. It inevitably harms people and amplifies dangerous tendencies because that makes them money.

Facebook can’t be fixed. It must be redesigned. We can’t just tinker a little bit with the algorithms and expect it to solve any amount of the issues we face. We can’t just tell Mark Zuckerberg to go to the timeout corner and think about what he did and expect Facebook to make any substantial change on their own. The federal government should and needs to step in to make sure solutions are carried out.

This leads us back to our question of a company’s relationship with their users. My answer is: a tech company should have an open relationship with their users. Facebook should state very clearly exactly what it is they desire from their users and how they manage their platform. Its users should decide whether or not they’d like to use this platform from that statement.

This is all in an ideal world, of course.

In the real world, Facebook is incredibly deceptive. Users are generally unaware of how Facebook influences their feed, their thoughts and their actions. Users unknowingly give to Facebook their data, their profile and their preferences. And Facebook takes what they want, when they want, using it however they want. Most often, they use it to get more out of the user: more preferences, tendencies and trends to sell to advertisers.

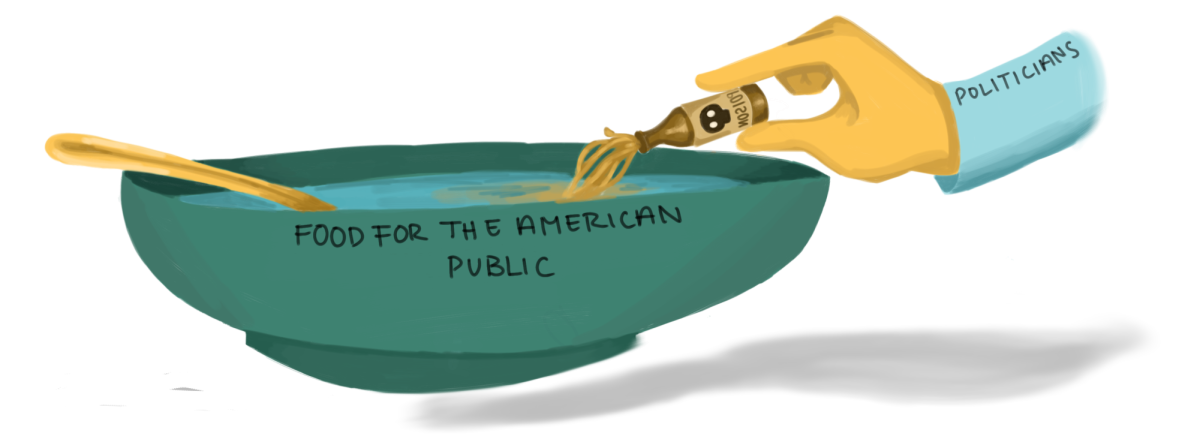

We need a third party in this relationship, whether it be the federal government or a separate organization. Because as long as the relationship stays between the user and the company, the company has all the power to manipulate the user however they see fit without the user suspecting a thing. A third party may be able to level the playing field in the relationship by checking Facebook and empowering the user to make their own decisions about their data.

In policy terms, this means regulation and oversight. This means intervention. This can’t be some slap on the wrist because we’ve known how that works out.

Frances Haugen is right about a lot of things, but she doesn’t dig her heel deep enough to encourage lasting change. And as predicted, Facebook shrugs, says their apologies and continues with business as usual. But of course our beloved Congress wouldn’t be biased and just let that go, right? Right?

In conclusion, I hate politics.