I hate airplane leg room.

Some three years ago, I was going to visit family in China. For those who’ve traveled to Asia, you know that it’s about a 24 to 28 hour span of just traveling, commuting or doing whatever it is just to reach your destination. And the worst part is definitely the long flight, where you sit for more than a dozen hours straight, only standing when you need to use the bathroom.

The main challenge of these international flights is finding a way to pass the time. Most people do the smart thing and sleep it off, but I’m utterly restless on airplanes. This leaves me with 14 hours all to myself, restricted to an economy class seat. I need something, anything, to distract me from how uncomfortable my legs are and the insanity-inducing airplane noises. Thankfully, our airline overlords offered us free movies.

Naturally, I was scrolling through United’s movie options, when I came across a peculiar film, “Crazy Rich Asians.” I’m not crazy rich, but I am Asian, so in an instant the decision was settled. I sat for two hours and stared at the seatback screen for two hours, completely entranced by the movie as to not even notice the annoying person who randomly opens their window to cloud gaze.

This movie hits every expectation I had going into it. It is crazy. It is rich. It is undeniably Asian. It is star-studded. It is extravagant. It is everything I wanted it to be.

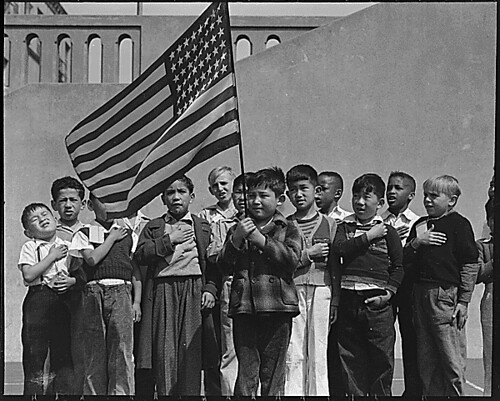

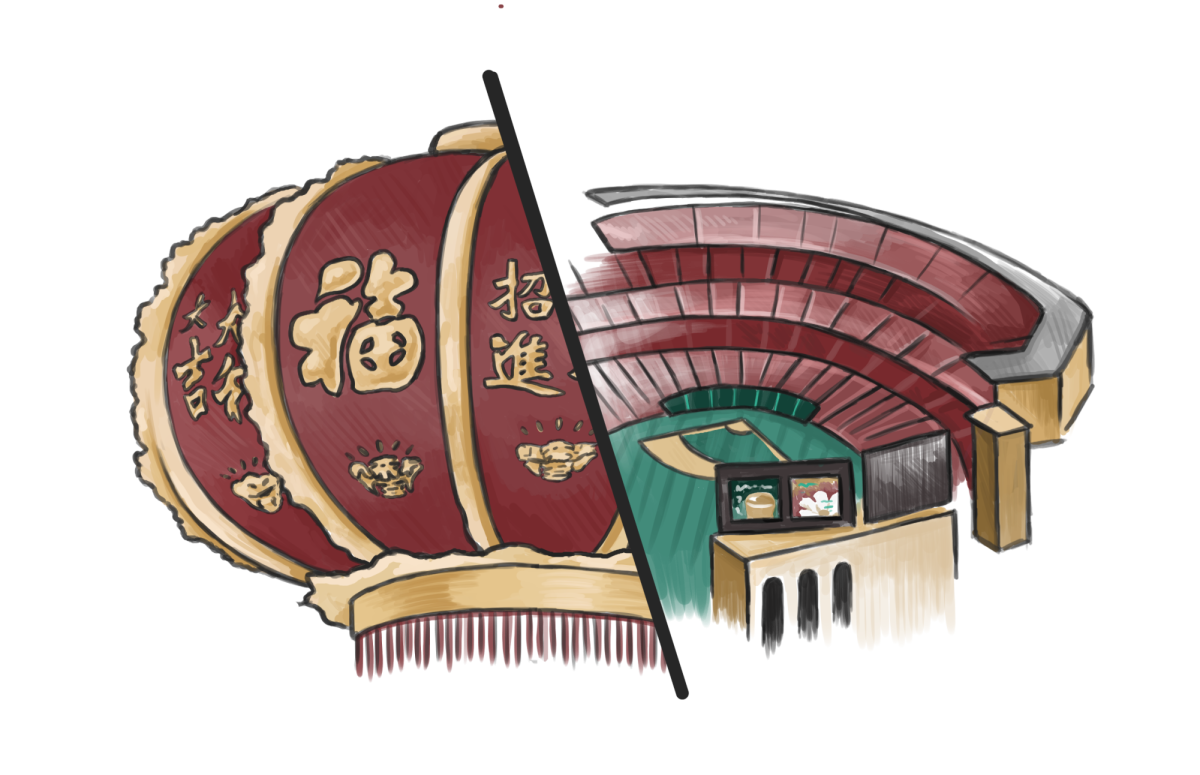

Two thumbs-ups to the romance. A head nod for the comedy. I enjoyed “Crazy Rich Asians,” the movie. But of course, unbeknownst to me, “Crazy Rich Asians” was regarded as more than just a movie. Director Jon Chu knew going into it the burden it must bear, with its primarily East Asian cast, its representational value and its cultural significance. In a sense, “Crazy Rich Asians” had to prove itself as more than a screenplay, but also a cultural staple like “The Joy Luck Club” was.

Many movie critics seemed especially aware of this, either purposefully deciding to avoid the question entirely or go all in, dissecting its “ground-breaking” nature. If you pay close attention, those who went down the latter often threw around the terms “Asian-American representation” or “strides for Asian-Americans,” treating this movie as an engine for social change.

“Crazy Rich Asians” is great, don’t get me wrong. But it isn’t significant in terms of representation. Unless you’re an East Asian multimillionaire, it’s going to require some mental gymnastics to relate to the movie. For 99.99 percent of us, there is no $40 million wedding, no yachts and no extravagance. The movie is a dream realized, with more ultra-high fashion than “The Devil Wears Prada” and more glamor than “The Great Gatsby.”

Even besides the lack of this degree of opulence in most East Asian lives, the movie hardly, or subtly, goes the distance to show South Asian or Malay populations that reside in Singapore, making the “Asian-American” word choice limited to one subgroup.

Representation isn’t just the fact that the actor is of a minority group. It’s also who they’re acting as, what they do and what they’re surrounded by. “Crazy Rich Asians” is a win for Asian-Americans in the media industry, but for audiences, it wasn’t much deeper than a great movie.

Working towards “Asian-American representation” in the media requires an interrogation of the term itself. What do we really mean by it? And are we accomplishing what we originally set out to do?

Trapezoids, too

It irks me to be called “Asian-American,” the “quadrilateral” of racial labels. It was once a radical label for uniting those of Asian descent against their oppression. But now, it’s become co-opted or perhaps sterilized to the point where anything with four sides and 360 degrees is “Asian-American,” with little space for nuance. The word has lost all meaning besides the stereotypes we’ve stuck onto it. And they’re exclusive stereotypes: only those who are within those contrived boundaries are known for being “Asian.”

What I assumed most people meant when they called me “Asian” was “Chinese,” which is a correct and fair assessment of my ethnicity, considering my appearance, so I thought. For a while, I just allowed the interchangeability of the two terms. At least, I gave the benefit of the doubt to the speaker that they acknowledge the multitude of cultures and people that fall under “Asian.”

Over and over, that assumption has been disproven. Saying “Asian-American” is a blank term to me. Asia is the biggest and most populated continent in the world. Be more specific.

Some people say “Asian-American” and refer to the first-generation immigrant experience as a whole. Some people say “Asian-American” to avoid trying to guess what kind of yellow I am. Some people say “Asian-American” and think the entire Asian continent is just 17.21 million square miles of Chinese territory.

Who do we want to see? It’d be a mistake to only count East Asian cultures, as if that was the only part of Asia that existed or mattered. And yet, that seems to be how we view the situation. Remarkable films for “Asian-American representation” host primarily East Asian casts: “Shang-Chi,” “Crazy Rich Asians” and “The Joy Luck Club” come to mind.

There are just better films in terms of representation that are hardly discussed and rarely emulated. “Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle” plays around racial stereotypes in a comedic and careful way, making sure to acknowledge Harold’s Korean background and Kumar’s Indian family while also not playing into the stereotypes. Showing the two leads as stoners first and Asian second made the film great, elevating the comedy and crafting characters for positive representation that extend to the South Asian community, not just the East Asian one. Obviously there isn’t one movie that could do it all, but at least we can take it one group at a time.

Just as the square isn’t the only quadrilateral worth mentioning, East Asians aren’t the only Asians worthy of representation. South Asian, Malay, Arab, Hmong, Cambodian, Vietnamese, Filipino and the dozens of other cultures comprising “Asian-American” are all equally deserving of screen time.

Talk like me

The other day, I came across a TikTok of some Chinese guy making jokes in what I call “Chinglish,” a mockery of the accent East Asian English learners often talk in. Besides the fact that it just wasn’t funny, it was downright abrasive.

It’s pretty obvious that the guy could speak English without the accent; he just chose to mock Chinglish for the “humor.” And the content played extensively on overused and saturated stereotypes: Asian kids have thin, slitted eyes and do their homework obediently, otherwise risking being spanked by their tiger mom. They get good grades or get disowned, eat rice, try not to be a disappointment and pronounce Ls incorrectly.

It reminded me of another similar instance. I was once at a meeting talking about Asian stereotypes when another Asian person chimed in and said, “It’s just Asian culture to be hard working.” I wasn’t really sure how to react. Perhaps it was with disgust, but more likely just confusion considering the context of the meeting.

On one hand is the caricature, used in “humor” and clearly exaggerated. And then there is the model, essentially the caricature but professionalized, official. Both are particularly sinister.

The two justify each other’s existence. The caricature is only acceptable because we know it is exaggerated and we know it is exaggerated because the model exists as a comparison. The model is only acceptable because it is a compromise between the supposed truths of the caricature and a post-racial societal norm of colorblindness.

They also perpetuate each other. Awareness of the caricature builds notice for confirmation of the model and vice versa. It’s one vicious cycle of confirmation bias and “pattern-detecting.”

These two archetypal stereotypes are so entrenched that it is even a common belief among Asians. It’s a shame that the most believed attribution to high achievement is simply race, genetics, culture, family or whatever stupid reason one wants to make up that isn’t just the ambition and passion of the person themself. When the entire genetics model eventually became socially accepted as the caricature, a new model appeared to replace it.

“It’s just Asian culture to be hard working.” Yep, the whole Asian continent is one diligent monoculture, you’re totally right.

When we portray Asian people in the media, it’s not enough to eliminate the caricature of the Asian, because some other notion will become caricature and the stereotype below it will become the model. It’s an infinitely regressive, infinitely plastic stereotype. When one is dethroned, another arises.

Most of the time, the new model is just a variation of the old. “Smart” became “hard-working.” “Obedient” became “over-achieving.”

At times we feel that we move ever closer to equality. Less and less are we caricatured, stereotyped, villainized or exoticized, so we think. But equality in this definition is equivalent to erasure; erasure of what it means to be Vietnamese, Desi, Arab, Chinese, Korean, Hmong, Filipino. Asian. Equality in this sense is simply becoming shreds closer to white, which inevitably means being less Asian. Harsh desires for white beauty, white status, white scholarship and white normativity are dichotomized with the Eastern standards, not by our fault.

There seems to be a general binary about how we can improve Asian representation in the media. There is the good way, which is to reverse or contradict stereotypes right on the big screen. And then there is the bad way, which is to continue to embrace current stereotypes. But neither way necessarily brings us closer to fairness. Of course, we ought not do what we’re doing. But there’s also no benefit in contradicting the current stereotype, as it never brings us closer to fairness — only closer to becoming white.

Running against the stereotype plays directly into the white standard. One of the most vivid examples of this is with the emasculation of Asian men. The age-old stereotype of the undesirable Asian man has led to a lot of self-hatred, a lot of insecurity among us. But the solution is not to play into the white heteronormative definition of attraction and sexuality in order to prove that Asian men are essentially sexy.

Matthew Salesses makes this point beautifully through analyzing Kumail Nanjiani’s character in “The Big Sick” and his courtship of Emily, a white girl, in “The Big Sick.” The movie demonstrates that Asian men are often portrayed as desirable in the way straight white men are desirable in order to become “masculine.”

“The film heavily links Kumail’s masculinity to the performance of race and sexuality — he picks up Emily after she jokes that he might be good in bed and he writes her name in Urdu,” Salesses writes. “For straight Asian American men, this means wanting to be wanted in the way white heteronormative men are wanted. If an Asian American man can win the love of a white woman, he thinks, then he might have a claim to America in all its whiteness and straightness and maleness after all.”

Instead of arguing the contrary, we ought to humanize Asian figures in the media.

Play by their rules and we inevitably lose their game. To create positive representation for Asian-Americans, creators have to play outside of, instead of contrary to, modern stereotypes. Otherwise, they face perpetuating some other rigid structure for our definition, build some other unrealistic expectation for Asian people or create some new insecurity for our generation. Turn 180 degrees and you’re still walking along the same road.

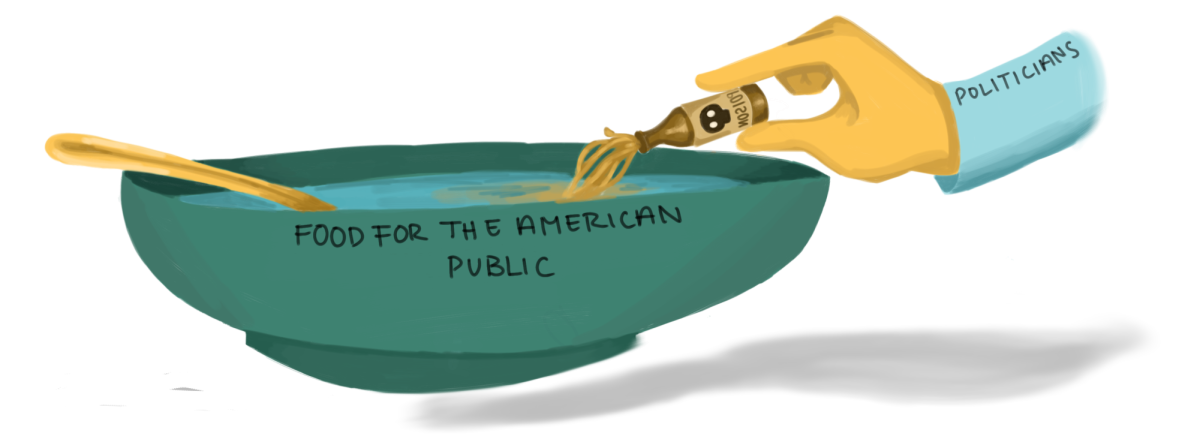

In conclusion, I hate politics.