How did Mansa Musa’s famous pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 affect modern tipping culture? The answer, of course, is not at all, but the fact that I actually had you for a moment there just goes to show how confusing tipping culture can be sometimes.

Tipping has been a subject of fierce controversy ever since it first became widespread in the United States following the Civil War. Supporters of tipping have long asserted its necessity to support underpaid workers and motivate them to work harder, whereas its critics argue that workers do not deserve extra money and certainly not from consumers. Clearly, one of these two must be wrong. Or perhaps they both are.

One of the first American businesses to encourage tipping was the Pullman Company, a railcar company which began hiring freed slaves as porters in 1868. To save money, the Pullman Co. paid its porters next to nothing and offset this by encouraging its wealthy customers to leave tips. According to the Restaurant Business Magazine, these practices saved the company $75 million (inflation-adjusted) in 1916 alone, and were used to justify measly wages. Tipping was soon adopted by restaurants and hotels and quickly became widespread across the hospitality industry, the restaurant industry and more.

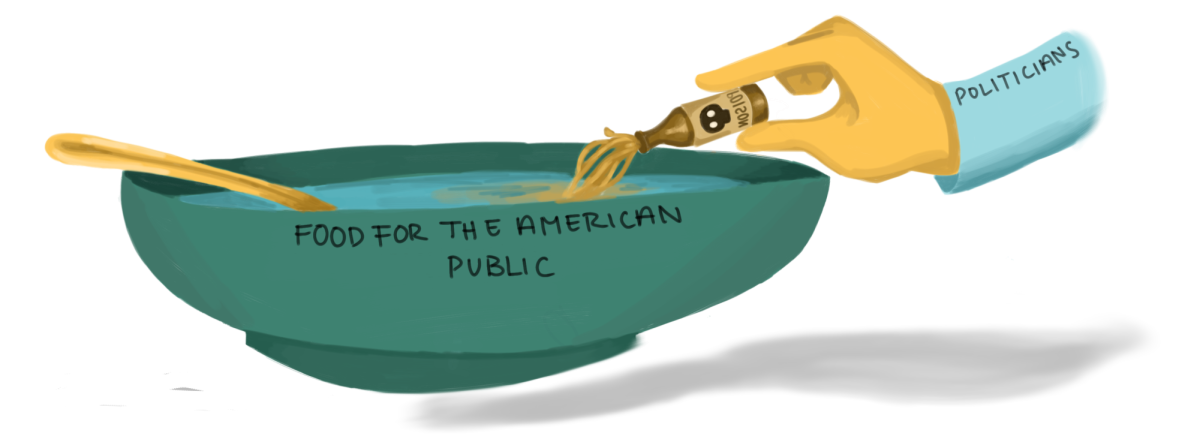

The only reason why the owners of so many companies would so rapidly adopt new policies would be to benefit themselves —and when they take a greater share of the profits, their workers are left with less.

The fact that tipping culture ultimately harms workers is further backed by analyzing our wage laws as a whole. The fact remains that American businesses do not need to pay tipped workers the minimum wage. When the Fair Labor Standards Act was first passed in 1938, a minimum wage was established to protect workers from the capitalist tendency to underpay them. However, tipped workers were conspicuously excluded. It was not until much later that a minimum wage for tipped workers was established, and even then, it was significantly below the normal minimum.

Even today, the inequality remains. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, the minimum wage for tipped workers is $2.13 per hour, whereas the normal federal minimum wage is $7.25 per hour. In other words: business owners save more than 70% off on wages when they allow their workers to receive gratuities.

But that’s not all. While tipping culture allows businesses to pay their workers low wages, it also works in reverse: these low wages are what made tipping culture necessary in the first place. This is the most insidious thing about tipping culture — it perpetuates itself. Under the guise of caring for workers, business owners have managed to boost their own profits by permanently shifting labor costs to customers.

Looking back at the history of tipping, it becomes clear that the widespread adoption of this practice in the United States was not based on the kindness of customers, nor was it a creative scam to get “undeserving” and “ungrateful” workers more money. Rather, it was the cynical calculations of bosses and executives that created this process. The ploy to replace stable, dignified wages with tips was designed by owners to benefit owners — at the expense of everyone else.

Workers deserve to have a stable income without worrying about the whims of consumers, and consumers should not be responsible for a worker’s wages. There is no reason to deny waiters, busboys and others in the hospitality industry what all others are guaranteed by law.

While tipping as an individual action helps underpaid workers, it cannot be denied that as a wider practice it only harms them in the long run. Hopefully, we will someday reform our minimum wage policies and end this centuries-long debate. Until then, tipping is bad, but tip.