An uncomfortable truth underlies vast swaths of the urban development in St. Louis. That truth is found in everyday life, from the woman that quickly clutches her purse as she walks by the man that has a different skin color, to the hushed, guilty tones that spawn from a questioning of why an individual decided to move to an area that happened to feel more “civilized.”

That truth is gentrification – the process where part of a city changes from being a poor area to a richer one, where people from higher social classes live. Gentrification continues to occur extensively in areas throughout St. Louis. For example, in the West End, early signs of gentrification have begun to show. Outside investors have begun to buy up large tracts of property, beginning a process which results in longtime residents being priced out as new, wealthier families move in.

Consensus on metrics or examples of gentrification are mixed, but many examples predate occurrences of gentrification happening today. The Botanical Heights neighborhood serves as a potentially clearer example of gentrification to some, seeing extreme redevelopment east of Thurman Ave. (Here’s an interesting, albeit a little strange article from the time). Areas west of Thurman Ave. saw less contentious redevelopment, but still with a 170% increase in white, middle-class residents, potentially leading for some to classify its development as an instance of gentrification.

More recently, the definition of gentrification has expanded to include “commercial gentrification,” in which traditional facets — businesses, churches and other services – are supplanted with businesses that tend to be more profitable for the locality.

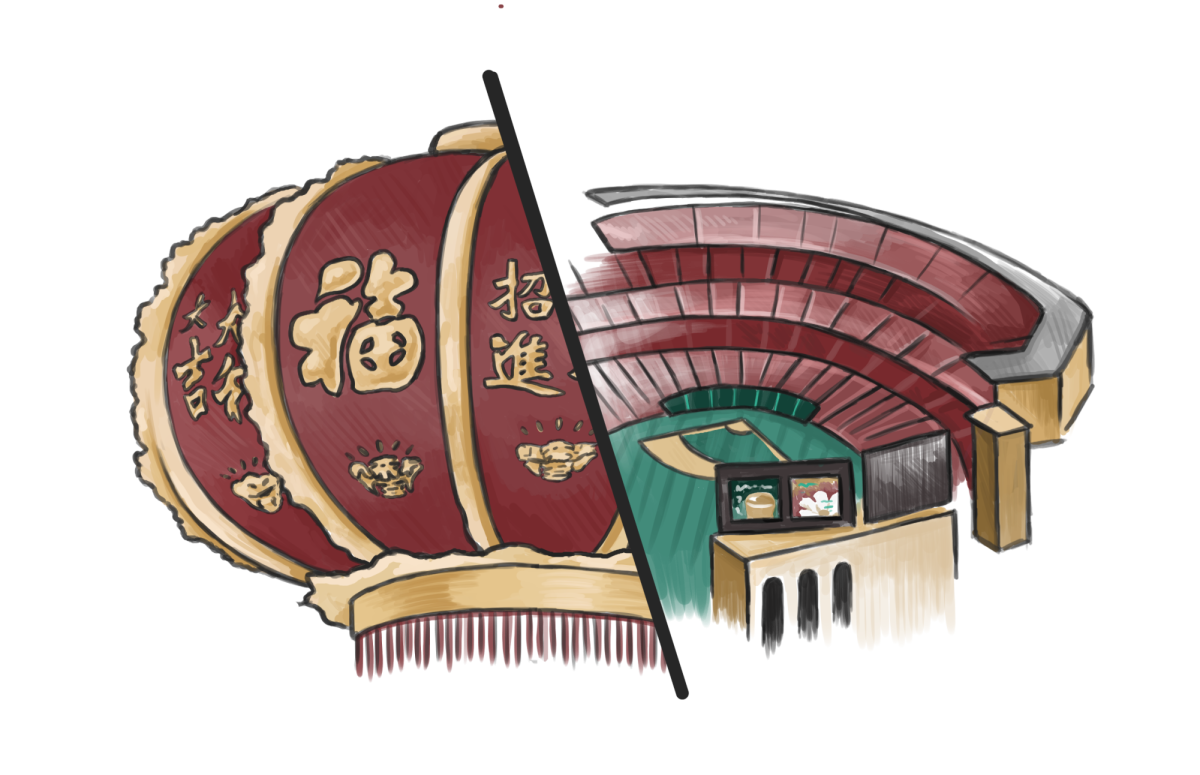

This type of commercial gentrification is extremely visible in St. Louis. Take, for example, the recent development of a new shopping district anchored by Costco on Olive Boulevard and Highway 170, a decision that resulted in several minority-owned small businesses being bulldozed, including the only Korean Catholic church in the St. Louis area. This is especially devastating given the fact that areas around Olive Blvd. began to act as a surrogate Chinatown only following the destruction of St. Louis’s Chinatown.

Whether it be through people moving or making new buildings, St. Louis has a history of replacement, where the need for progress often overtakes the needs of its people. Despite any argued positive effects like increasing property values, gentrification often results in residents being priced out of areas, cultural erasure and destruction of an area’s history – all while the sacrosanct march of progress continues on.