When I was a kid, I immersed myself in fiction, escaping into books, movies and TV shows where I would place myself into the stories of the characters I saw: heroines with bravery, ingenuity, … a light complexion and blond hair. I inevitably imagined myself as a white girl, leading to an uncomfortable disassociation with my own skin. I soon realized that these were not my stories and were never intended to be.

Now as a teenager, Hollywood has made strides in casting more people of color, from 2016’s “Hamilton,” to the regency drama “Bridgerton,” and, more recently, Disney’s “Percy Jackson and the Olympians.” All these stories feature people of color in prominent roles, employing what is known as color-blind casting, which favors casting the best actor regardless of cultural background, allowing actors to portray characters of a different racial identity. Yet, even this representation comes with a caveat: these stories were never written with people of color in mind.

Color-blind casting is often regarded as progress, an act of subversion that normalizes something other than the white standard. The Black and brown founding fathers of “Hamilton” make the story of America more inclusive. The prominence of a Black Queen Charlotte and the Indian Sharma family in “Bridgerton” enables racial minorities to immerse themselves in an traditionally euro-centric era. The diverse cast in the new Percy Jackson adaptation makes an attempt at correcting the racial homogeneity of the original book series.

However, despite its intentions, color-blind casting can still exclude roles and stories from people of color. In the past decade alone, Natalie Portman, Emma Stone and Scarlett Johansson, among others, played characters on screen who were of Asian descent in the source material. Color-blind casting indeed works backwards, leading to a disregard for cultural identity. Moreover, color-blind casting can lead to a collusion of different cultures, as seen in “Emily in Paris,” where Ashley Park, a Korean-American actress, portrays Mindy Chen, a Chinese character. One act of blindness can lead to another.

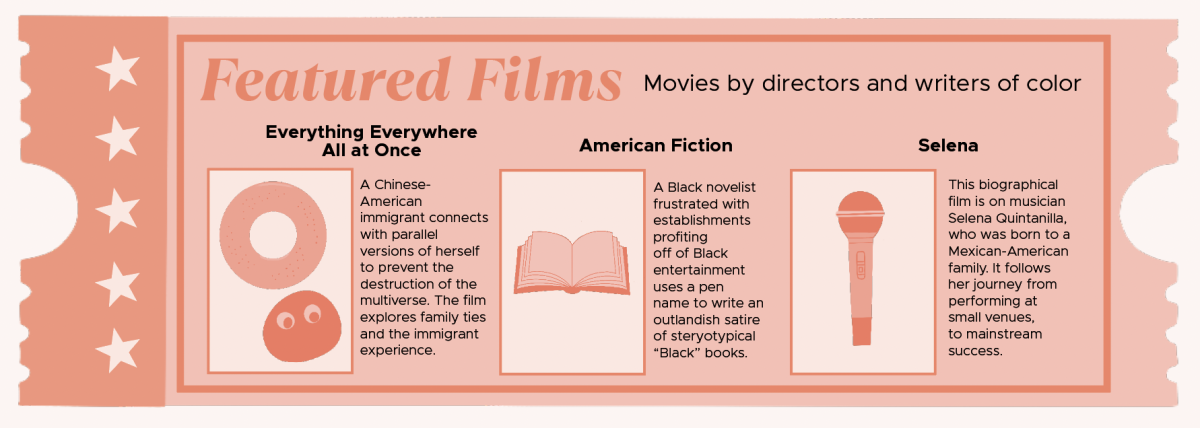

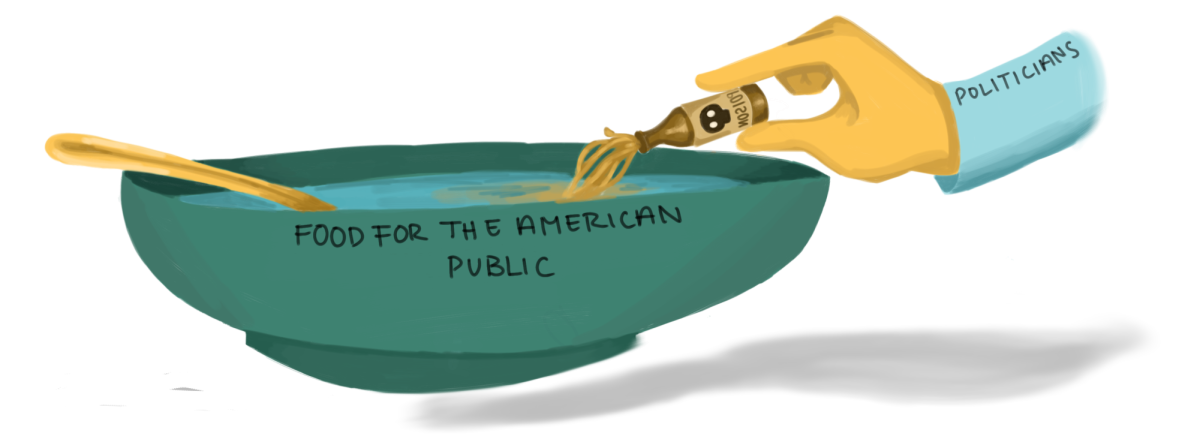

Any casting of a performer in the role of another race forces them to approximate the lived experience of a culture that isn’t their own. The industry assumes that by giving a role, any role, to a person of color, they’ve fulfilled their “diversity quota.” Color-blind casting encourages production companies to continue pushing for “white stories” under the guise of racial representation rather than creating authentic stories from directors and writers of color. Ultimately, this perpetuates a larger problem within the lasting narrative of America, a seemingly white story with people of color haphazardly slotted in.