Do the words ‘American Chestnut Tree’ ring a bell?

Probably not.

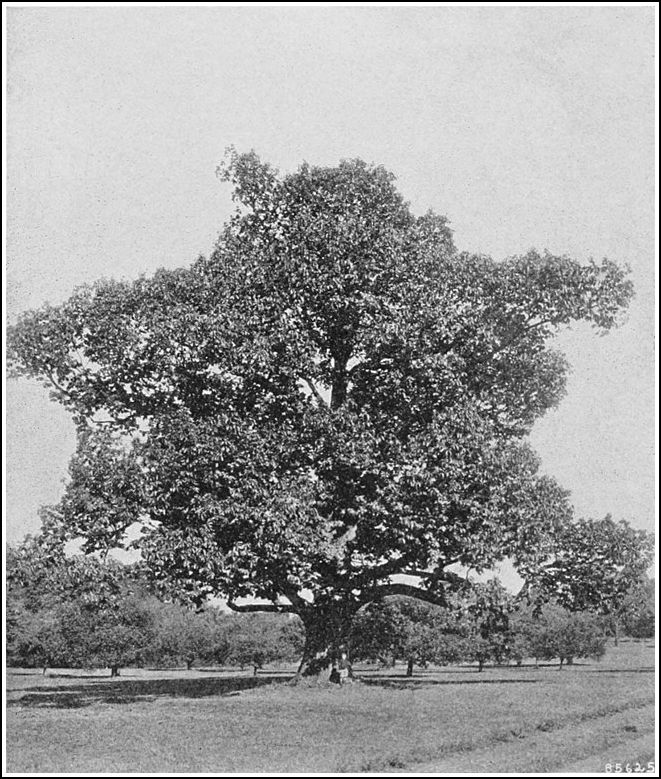

The American Chestnut, or Castanea dentata, discovered in 1904, used to cover the eastern US. There were four billion of them, and now, the tree is critically endangered in both the US and Canada.

Castanea dentata is a quickly-growing deciduous tree, reaching up to almost a hundred feet with straight and rot-resistant grain. It was important to the animal populations that lived in forests containing the tree, with the chestnuts feeding wild deer, turkey, and bears among other populations, and also provided large amounts of nutrients to the surrounding soil.

There once were four billon of these trees, spread in great forests ranging from Maine to Mississippi, until a fungal blight (Cryphonectria parasitica) introduced to the US through imported Asian chestnuts killed off nearly all of them.

Technically, the species is not necessarily ‘extinct’- rather critically endangered- because rather than ceasing to exist, American Chestnut Trees can still be found where they used to grow- but they are unrecognizable. They exist as little more than bushes and stumps, just barely surviving. Growing any taller is out of the question.

When these trees died off, it had widespread effects. The American Chestnut’s wood is straight-grained, giving it an extra edge of quality as opposed to other kinds, quickly growing, sturdy, and rot-resistant. It was used to build houses, posts, and even railroad tracks- and the towns that lived near these incredible forests gained huge boosts and viewed success in their economy because of the tree. This means that when the species died off, these towns suffered greatly. The once incredible effects that served the economy, suddenly turned for the inverse.

In addition to hurting the lumber industry, the extinction also caused great swaths of animals/livestock to die off. On the American Chestnut Foundation’s website, the history page details that ‘Hogs and cattle were often fattened for market by allowing them to forage in chestnut-dominated forests. Chestnut ripening coincided with the Thanksgiving-Christmas holiday season, and turn-of-the-century newspaper articles often showed train cars overflowing with chestnuts rolling into major cities to be sold fresh or roasted.’ So naturally, when it died off, this other effect caused waves as well.

An organization called The American Chestnut Foundation, or TACF, is working to revive the American Chestnut Tree, by adjusting the genome to create a version of the species that can resist the blight that once killed it off.

TACF was created in 1983, and to this day works toward the restoration of the species. Their main approach is titled 3BUR, for Breeding, Biotechnology, and Bio-control.

The first operation, Breeding, is conducted on a research farm located in Virginia, near the small residential town of Meadowview, with the most recently recorded population (from the 2010 census) of 967. In addition to the main station, TACF also carries out breeding research in sixteen locations across what used to be the American Chestnut’s natural range.

They state that ‘our breeding efforts are focused on further improving blight tolerance and incorporating resistance to Phytophthora cinnamomi… we are using genomics to increase the speed and accuracy of selecting trees with the greatest tolerance to chestnut blight and root rot.’

The Oxford Dictionary states genomics as ‘the branch of molecular biology concerned with the structure, function, evolution, and mapping of genomes’.

Biotechnology comes next, relating to the science of transgenics, in which new biological material is introduced to a sample to modify the DNA structure and create new or improved features in the species. It is the same style of science as introducing human diseases unto rats to produce possible vaccines.

The foundation’s scientists at New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF) discovered a gene sourced from wheat that enhance resistance against blight, and with the layering of other genes, TACF predicts that they can obtain government approval to go ahead and plant the trees created from these transgenics ‘in three to five years’.

Then there’s biocontrol, or, in the way TACF is pursuing it, ‘hypovirulence,’ in which the fungal disease that was responsible for the extinction in the first place, is itself infected by a virus. The virus attacks the fungus, and reduces its capability to harm new growths of the American Chestnut.

The report about 3BUR concludes by stating ‘While no single intervention can completely eradicate chestnut blight, together the science of breeding, biotechnology, and biocontrol (3BUR) offer our best hope for rescuing the American chestnut tree.’

Then they encourage you to donate, which I did happily.

And you should too.