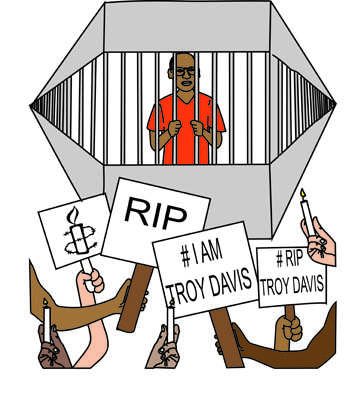

After 20 years on death row and three postponed executions, Troy Davis was executed Sept. 21 in Georgia, maintaining his innocence until his death. Davis was convicted for the murder of police officer Mark MacPhail in Aug. 1989, despite evidence suggesting Davis’ innocence.

Davis served 20 years on death row, and his sentence led to an ultimately unsuccessful campaign to reverse his conviction. On the night of the execution, the Supreme Court reviewed a petition from Davis’ lawyers, postponing the execution by a few hours and renewing hope that Davis might not be executed, but chose not to act on the request. According to Davis’ 1991 conviction, Davis shot MacPhail, who had a second job as a security guard, in a parking lot as MacPhail attempted to assist the victim of a beating. During the trial, witnesses testified that they saw Davis shoot MacPhail, yet the prosecution produced no physical evidence linking Davis to the crime, and all but two witnesses later withdrew their statements. The uncertainties that arose after the verdict led to three stays of Davis’ execution and multiple appeals to higher courts and convinced many that Davis was innocent.

“I just believe that an innocent man was put to death,” senior and Ladue African American Students Association chairman Charlene Masona said. “The death penalty in general shouldn’t be legal because it is still taking someone’s life. The whole situation was tragic and I feel that America’s justice system is failing time and time again.”

Though the appeals did not reverse Davis’ sentence, Davis’ lawyers, along with anti-death penalty organizations like Amnesty International, delayed the execution for four years after the initial execution date in July 2007. Davis’ defense could take no further action when the Supreme Court rejected Davis’ appeal on the night of the execution.

“The campaign to halt his execution failed because there was no legal intervention that could be made that wasn’t already made,” social studies teacher and Amnesty International club sponsor Eric Hahn said. “For example, I know the governor [of Georgia], who has been requested to stop the execution, didn’t do it. I believe Amnesty asked President Obama [to intervene]. He said it would be inappropriate for him to override a state decision.”

However, throughout 20 years of attempts to overturn Davis’ conviction, including multiple appeals to the Supreme Court, his initial conviction remained standing. When Davis appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit in April 2009, the court wrote in its decision, “When we view all of this evidence as a whole, we cannot honestly say that Davis can establish by clear and convincing evidence that a jury would not have found him guilty of Officer MacPhail’s murder. We are also unpersuaded by Davis’s suggestion that his claim of innocence has not been and will never be heard. As the record shows, both the state trial court and the Supreme Court of Georgia have painstakingly reviewed, and rejected, Davis’s claim of innocence.” Some theorize that if the evidence did indicate Davis’ innocence, his advocates would have successfully overturned the decision over the course of 20 years of appeals.

“I can understand why people are really upset about this,” senior and Young Republican member Katie Huey said. “It’s a tragedy every time a human life is lost. I do think they made a bigger deal about this case than they should’ve. … It was originally twenty years ago, and if they appealed for twenty years and nobody was able to overturn it, maybe he was guilty.”

Doubts about Davis’ guilt led Amnesty International to use Davis’ example to push for the abolition of the death penalty. In the hopes of halting the executing, Amnesty International collected and sent over six hundred thousand letters to the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Parole requesting that the execution be delayed. The organization encouraged those against Davis’ sentence to sign an online petition in favor of abolishing the death penalty called the “Not In My Name Pledge.” The immense for support for Davis has encouraged Amnesty that the support for their fight to eliminate capital punishment will grow in the future.

“We got a lot of support. People are kind of energized by that. … They’re outraged that it happened. … There’s been an outpouring of support for him,” Brian Evans, the campaign manager of Amnesty International USA’s Death Penalty Abolition Campaign, said. “We feel really energized by that. … We feel like going forward there’s a much larger group of people ready to take action to stop it.”

Momentum for abolishing the death penalty shows no sign of slowing as a result of Davis’ death. Recently, more states have begun to reconsider the death penalty, a positive signs for anti-death penalty advocates.

“I think the campaign to abolish the death penalty will not stop as a result of Troy Davis’ execution,” Hahn said. “As a matter of fact, I think there has been a number of state that have abolished the death penalty or have said we’re going to stop all cases of death penalty right now for further review, which could be indefinite.”

Anti-death penalty advocates have successfully abolished the death penalty in 16 states, but have yet to eliminate capital punishment in the remaining 34. However, the process of prohibiting a practice across the U.S. can be lengthy given disparities in states laws.

“I think that as opposed to countries in Western Europe, the U.S. is culturally different,” Evans said. “We have a long history of slavery and our political system is set up to keep people under control and the death penalty is an extension of that. We have a system where each state has to abolish the death penalty itself. We have abolished the death penalty in 16 states [but] we have to abolish the death penalty 34 times, so it’s much more difficult than in a place like France.”

Like Georgia, Missouri administers capital punishment by means of lethal gas or injection. According to a document on the history of the death penalty in Missouri published by the Missouri Department of Corrections in February 2011, “Prior to [September 1937], criminals in Missouri were executed by public hangings, conducted by the Sheriff in the county where the crime was committed.” Missouri stopped administering the death penalty after a 1968 Supreme Court declared the practice cruel and unusual punishment, but resumed the practice in 1976 upon the Supreme Court reversal on its earlier ruling. Since 1976, Missouri has executed 68 people, the fifth most executions of all states.

Amnesty International celebrates its fiftieth anniversary this year, and abolishing the death penalty was among six focus campaigns chosen to celebrate the anniversary. Ladue Amnesty discussed the Troy Davis case Sept. 22 at their second meeting of the year. Initially, Ladue’s Amnesty International chapter planned to focus on women’s rights in Nicaragua for the month of October, but subsequently shifted to focus to Amnesty’s abolish the death penalty campaign.

“One of Amnesty’s big campaigns this year is working to abolish the death penalty, so we’ve used his execution to initiate discussion about that and create awareness about the issue: whether the death penalty can ever be applied fairly, whether humans ever have the right to apply it, and the high cost it imposes on state budgets,” junior and Ladue Amnesty vice president Emma Grady-Pawl said.

Some Amnesty members, including juniors Lizzy Wallis and Isabella Benduski, feel that Davis’ execution was unjust view the case as an extension of a problematic judiciary. They see the verdict as a result of an unpredictable and inconsistent court system.

“America’s court system has too many unreliable factors to insure for a proper trial,” Benduski said. “The witnesses, jury and evidence are all things that have an impact on the trials’ outcome. Unfortunately for Troy Davis, his trial may have been swayed in the wrong direction by unreliable, biased information.”

While Troy Davis was executed, his cause nevertheless inspired discussion about the death penalty. Those against capital punishment often argue that death is irreversible and that retaliating against crime with another crime is hypocritical.

“I strongly am against capital punishment because I don’t believe we should justify a crime by committing another crime,” Wallis said. “Once something so permanent such a murder is committed, there is no turning back, so if the person turned out to be innocent, there is no way to bring them back to life. I believe sentencing the person to prison for life would be a worse punishment because they would have to actually think about and face what they did rather than just being killed and running away from it.”

However, proponents of the death penalty believe otherwise. Supporters reason that the death penalty deters crime and that those who commit monstrous acts deserve the ultimate punishment.

“I am typically against it, but I find there to be some circumstances in which I believe it is justified,” junior Meredith Behrens said. “I believe it’s justified when the killer creates a situation of unfathomable suffering for the victim, when the killer’s actions create a level of suffering that you can’t even comprehend what the victims must have gone through at the killer’s hands.” #

Troy Davis execution raises international outcry

0

Tags:

More to Discover