In its lawsuit against Missouri Senate Bill 54, the Missouri State Teachers Association was granted an injunction, August 25. The injunction, regarding section 162.069, will last until Feb. 20, 2012.

Sponsored by Senator Jane Cunningham (R), 162.069 bans private contact between teachers and students online and requires districts to form social media policies.

The section was addressed in a special session in the Missouri General Assembly the week of September 6-9. The future of the section is unclear, though the bill has been renamed Senate Bill 1. However, in an August 26 statement on his website, Gov. Jay Nixon said that he will ask sections 1 through 4 of 162.069 to be repealed. The General Assembly also has the option of rewriting portions of the bill.

“The injunction entered on Friday in the state court case is a great victory for all teachers; however, it is not a permanent solution,” American Civil Liberties Union lawyer Anthony Rothert said.

Since the bill was signed by Governor Jay Nixon, two lawsuits were filed, one in Missouri state court by the MSTA and one in US federal court by the ACLU.

“On the whole, the bill does a lot to protect students, does a lot to protect teachers,” MSTA Online Community Coordinator Aurora Meyer said. “The language and policy of the social media portion are where we have some concerns.”

Before the injunction was granted, 162.069 would have gone into effect August 28, and district policies would have been expected by January 1, 2012. Though 162.069 is being discussed, the rest of the bill will go into effect.

“I’m personally aggravated that we need to write these laws, they seem to be a substitution for good judgement on the part of the teacher. The idea of the assumption [is] that teachers are not using good judgement,” English teacher Kim Gutchewsky said.

Cunningham said the Bill originated to stop sexual misconduct in schools and that 162.069 was added two years into the bill writing process. Bill 54, based off statistics gathered from 2001-2005, also addresses the concept of ‘passing the trash’, or maintaining transparency in hiring practices within districts and stopping prevalent sexual misconduct

“The Associated Press a few years ago did a five year study on sexual misconduct in our public schools, and they reported in 2007 that over 2,500 educators lost their license for sexual misconduct in our public schools and then you bring that down to Missouri, we were the 11th worst state in the nation,” Cunningham said. “87 educators lost their licenses during that time period for sexual [mis]conduct. Just this last Tuesday, the department of elementary and secondary educator just took the license away from two teachers for sexual misconduct. It’s prevalent; it keeps going. It’s not isolated, parents wake up, school districts wake up, it’s extremely prevalent, and it’s growing up to the minute.”

Not everyone agrees with Cunningham regarding the problem of sexual misconduct, particularly its online aspects. ACLU lawyer in the lawsuit Anthony Rothert said that portion 162.069 does not solve any real problems.

“Many aspects of this bill are directed at real actual problems, and they’re great, that’s government at it’s best addressing real problems,” Rothert said. “The communication aspect in the bill only addresses imaginary problems.”

162.069 caused controversy which overshadowed the bill’s other portions. Most of the controversy stemmed from two areas of complaint: vagueness and infringements on First Amendment rights.

“The bill of course is much too restrictive,” social studies teacher Robert Snidman said. “I question whether or not the bill will stop the criminal activity it is trying to prevent.”

Though the bill applies to all of Missouri, school districts were left to create their own policies, which raised concerns across the state regarding the bill’s vagueness. This requirement could create a potentially wide range of district policies.

“Any time you make a law and there’s so many questions about it, there’s a problem,” Ladue superintendent Marsha Chappelow said. “We want to question the intent and whether it was properly written. I think the original intent was for student safety, but I think that got lost along the way.”

The MSTA lawsuit was filed after teachers lodged complaints with the MSTA. Meyer said that many school districts already have social media policies, but that concerns about restrictions were raised.

“If the bill had just said that school districts need to set their own policies, no problem with it,” Meyer said. “When we get concerned is when they start going into specifics of what is allowed and what isn’t allowed. A lot of teachers are also parents, depending on how one reads the law, they can’t be friends with their own children if [they] go to the school district.”

The same day the MSTA lawsuit was filed, Ladue Middle School communication arts teacher Christina Thomas filed the lawsuit represented by the ACLU, after they contacted her. Thomas had concerns about Ladue’s plans and setting restrictions on staff in the district.

“I knew Ladue wouldn’t be upset that I did this, since it’s not just about the school district, it’s about the law and the interpretation of it,” Thomas said.

In order to comply with the state requirements, Ladue sent a memorandum to staff August 9, explaining the law and laying out expectations for behavior. One of these expectations states that “teachers may not ‘friend’ even their own children on a Facebook or other social networking site, if their children are students or former students, as defined by law.”

“Communication with students should be private, yes, but once you hit a certain age, I think that’s up to the parents to figure out if there’s a concern,” Thomas said. “The thing is it was prohibiting what I could do as a parent, and I’m not okay with that.”

Sophomore Justin Cole agrees that Ladue’s policy based on the bill is too restrictive.

“I don’t think that Ladue nor the government has the authority or the capability to govern whether teachers can talk to their own kids on Facebook. If the government begins to intrude on such routine things in our life as Facebook, there is no telling how far they could go to eliminate our freedoms guaranteed to us from the Constitution,” sophomore Justin Cole said.

A Facebook group created by Marquette High School alumna Cameron Carlson became a watch center of the lawsuits for teachers, students, parents and lawyers from multiple districts. Through a letter writing campaign, petition and discussion boards, it has been crucial in sharing details about the bill and its implications.

“Tony Rothert from the ACLU contacted me and he said that he found out about the bill because of our group and that he was going to be taking on the case,” Carlson said. “Then after I knew the ACLU was on board, I contacted the MNEA and the MSTA, who wanted to support our cause. The controversy around the bill, in my opinion is good. Not only does it make people interested go out and do their research, but it also forces constituents to actually get involved in the legislative process. ”

Just as the bill’s text and the ACLU lawsuit remain in flux, so does the nation’s reaction to Missouri’s one of a kind bill, having received national media coverage on CBS News and the New York Times. Cunningham said that much of the controversy is misguided and disappointing, as the specific section is secondary to the rest of the bill.

“Some people I can tell by their comments and questions haven’t read the bill,” Cunningham said. “There is some misinformation being distributed, either out of ignorance or out of purposefulness. There is a Missouri teacher, [who is] the reason I got on TV, because this teacher put misinformation about the bill. He told educators [it] prevents friending… that is incorrect information that you just gave. It does not stop a teacher, it is perfectly fine under the law. They had lied… I was able to correct it on national TV. I’ve gotten great publicity.”

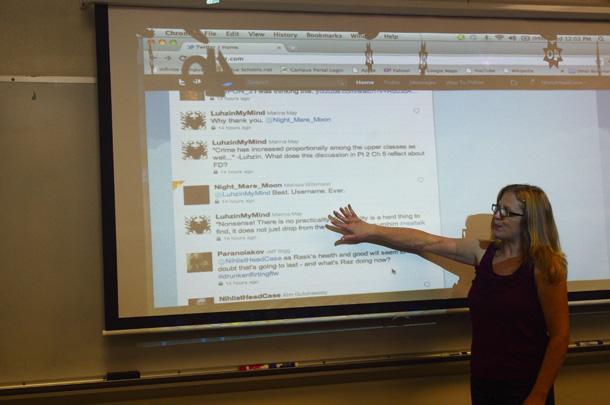

While discussion continues online and in law offices, the classrooms of Ladue are buzzing. At the start of the year, students were told that they must use their school emails to contact teachers, and some teachers have discussed the bill in class.

“I understand the reasons for the policies we have in place, but I do think it poses a hassle when students have to check different emails that aren’t allowed to be forwarded to main accounts, and instead of having a normal class group on Facebook, teachers must resort to other methods such as Twitter (which not everybody knows how to operate) in order to effectively teach their students,” senior Lila Greenberg said.

Not only do some teachers feel that their First Amendment rights are being violated, some students feel that they have lost the right of privacy. Because of the efforts to stop ‘hidden communication’ all emails and texts must be visible by a third party or server.

“I thought the law was pretty good at first, at least, a good idea, but I don’t really agree with how they’re doing it,” senior Chad Davis said. “I don’t like how parents have to be part of our emails… we can’t have private communication [with teachers], so I feel like if we do it over the school email, that’s good enough already, since the administration can check it.”

As online content and social networking become even more prevalent, schools will need to adjust their use of technology in the classroom. This year important strides have been made, including increased use of Google Docs and a Ladue seniors Facebook page. Teachers Debra Carson, Kim Gutchewsky and Jennifer Hartigan are using school-approved class Twitter streams to add another layer of communication with students.

“I’m concerned that it will make communicating with teachers a lot more difficult. Communicating with teachers is one of the most important things in regard to learning. Restricting this is inhibitive to learning,” senior Jerry Thomeczek said.

Bill regulations also affect club interactions. Communication via texting or over the Internet can be the fastest way to communicate a change of activity plans, or to provide updates for members.

“The way the bill has affected me is that it also applies to texting students,” math teacher Debra Carson said. “I run clubs and organizations-this also applies to coaches too- and I should be able to text the students in those clubs. If we’re out of town, calling their parents isn’t going to help.”

Though a controversial situation has ensued, the bill and its surrounding conflicts have raised an issue of the purpose and role of technology in the classroom.

“Technology is all around us and part of society… since it’s the way we think and interact and do things we’ve got to be able to teach kids how to use it appropriately. Then there’s the social networking piece. That’s how kids communicate; why shouldn’t we try to reach kids using that? There’s some scary parts about that. We’ve got to figure out what that means and how to be careful,” principal Dr. Bridget Hermann said.

While Ladue adapts its technology, Bill 54 has opened up a discussion that could lead to other positives in the future.

“Any time you have questioning, where people look at a subject in a new way isn’t bad,” Chapplow said. “Maybe all of us come out of this a little better off knowing what social media can and can’t do. Teachers may have changed how they’ve used social media, so I think that’s a positive ramification that could come out of this.”

The ultimate impacts of 162.069 are unknown, both on Missouri and the Ladue district. Rothert said that the ACLU lawsuit is pending, based on what happens during the special session. Many said that they do not think that section 162.069 will fix any problems.

“If creepy people are out there, they’re going to be creepy,” Carson said. “They are just going to have to be more creative, and find a way to do what they were doing before. I really don’t see the benefit of it.”

As the bill is currently being reworked, the final version could still set limits or boundaries on student-teacher contact online. This leaves districts waiting to see how their school could be affected by the bill and any future changes.

“We were actually waiting for some guidance… at this point we wouldn’t enact anything. We have several policies that are already in place, but we would not go forth with any new policies for sure until this is clarified,” superintendent Marsha Chappelow said. #

Legal 411

With two lawsuits questioning section 162.069 of the bill, the differences and overlapping areas of the case can be confusing.The lawsuit filed by the Missouri State Teachers Association received an injunction from Cole County Circuit Judge Jon Beetem August 25. Essentially, an injunction is an order issued by the court that orders the defendant to take a specific action.In this case, the controversial section limiting contact between teachers and students on social networking sites will not go into effect until Feb. 20. Until that time, legislators will be able to discuss and potentially rewrite the bill.

“In the long run we hope… to determine constitutionality, which we believe it is not,” Online Community Coordinator Meyer said.

The injunction has postponed the deadline for school district policies, but has also temporarily stopped the ACLU lawsuit filed by Ladue Middle School teacher Christina Thomas. Rothert said that the status of their lawsuit is still pending. Though both lawsuits focus on section 162.069, they are very different. The MSTA lawsuit is in the state court system and targets the vagueness of the law. Thomas’s lawsuit, however, is filed in the federal court system, and questions the constitutionality of the law.

“Our concern is that the law violates the first amendment because it’s written very broadly and very vaguely in a way that will require teachers to censor themselves and prevent… expressing themselves,” ACLU lawyer representing Thomas, Anthony Rothert said.

Key Players

The Missouri State Teachers Association was consulted in the drafting of the original bill, but due to a disagreement about section 162.069, they filed a lawsuit against the state which received an injunction in late August.

“We heard from a number of our members that they had questions and concerns and that they wanted some action.The law’s really vague and they’re not sure what they [need to] do to comply, and they need clarification. Our members asked us to be proactive,” Aurora Meyer said.

The American Civil Liberties Union is representing Ladue teacher Christina Thomas in a lawsuit against the Ladue School District. This lawsuit is running parallel to the MSTA lawsuit.

“Our lawsuit is a class action. That means it is brought on behalf of all Missouri public school teachers. The court has to approve, or certify, a class for a class-action suit. That typically takes several months to happen,” Anthony Rothert said.

The bill is sponsored by Senator Jane Cunningham, a Republican Senator representing the 7th district, a portion of St. Louis County, since 2008. She believes that inappropriate student-teacher relationships are “extremely prevalent,” and that the bill addresses that.

“It seems very strange and hypocritical to have MSTA have participated in crafting legislation for four years and to go on record endorsing it, to now be suing over it. It’s like trying to kill their work,” Cunningham said.

Road to the bill

Writers spent four years crafting Senate Bill 54, also called the Amy Hestir Student Protection Act. The bill centers around a story of a student who was sexually harassed by her art teacher over 30 years ago. It is sponsored by Senator Cunningham, with support from Chris Kelly (D) in the House. During the writing of the bill, MSTA and NEA were consulted. The bill was passed unanimously and signed by Gov. Jay Nixon, but controversy arose when the public began to foresee complications with its regulations.