In a house in Guanacaste, Costa Rica, small hands push a window open. Then another. Then one more.

Soon, the entire house is open, dewy morning air and soft light filtering in. The little girl props open the front door, completing her routine. She pauses outside. Cocks her head. Listens. The song of the day slowly meets her. A mix of neighbors chatting and cars rumbling floats by, punctuated by a staccato of bird chirps and dog yips.

“Maritza,” her mother calls.

And so, the day begins.

Spanish teacher Maritza Sloan grew up on the North Pacific side of Costa Rica. She was one of four children in her family, two brothers and two sisters, and her father worked a job that required weekly travel.

“I grew up seeing my dad Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays,” Maritza said. “He was working with a company that was in charge of putting electricity in, so he was always in different parts of the country. Sometimes he was farther away so he [came home] every other week. My mom was a seamstress, so we spent more time with my mother than my dad on the weekends most of my life.”

Maritza felt the effects of her father’s absence. Though she and her mother talk on the phone almost every day now, growing up, their relationship was not without its challenges.

“[I had a] very controlled life,” Maritza said. “My mom, especially being by herself most of the time, always felt like she had to protect her two girls. When my husband and I were dating, we were chaperoned the whole time. He had to come home and ask my mom permission to date me, and there was always somebody around us. We were never by ourselves. It was a very traditional way for people in Costa Rica [for] my age at the time. Things are not the same anymore, but I think about my husband and how weird this must have been [for him].”

Maritza’s husband, John Sloan, grew up far from Costa Rica. He lived on a farm in central Illinois and completed his Bachelor’s degree at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. After graduating, he joined the Peace Corps and served in Guanacaste, where he learned Spanish and met Maritza.

“I’d sit out on the street and play my guitar at night,” John said. “This was before [the] internet and everything. I got to know [Maritza’s] brother first, and then he invited me over to their house, and that’s how I met Maritza.”

After dating for about a year, Maritza and John moved to the United States and got married. In Texas, where they first lived together, Maritza focused on learning English and jump-starting her new life.

“I was always lucky that I came here for love,” Maritza said. “I married my husband, so he was always teaching me things about the [United States] culture. Also, I was a very independent woman. So from day one, I knew I had to get behind the wheel and start driving and doing those things that I didn’t do in Costa Rica, [like] learning the language [and] going to school. I wanted to finish my degree, so I knew I had to do that as soon as I got here. There was no time for me to waste.”

Soon, Maritza and John moved to Oklahoma, where John completed his PhD and Maritza completed her undergraduate education at Oklahoma State University. This was also where Maritza began teaching for the first time, spurred by her positive experience learning English.

“We went from the South to the North, back to the South and now the Midwest,” Maritza said. “Every place I went [was] like a window. You start seeing and learning about different ways of living, even in this country. Life in Texas was completely different than our life in Oklahoma. And so was life in Minnesota. I had to learn different styles of living. They all have given me different perspectives of life and [allowed me to] meet different people. I have friends all over.”

While they lived in Texas for the second time, Maritza and John had their daughter, Christina, causing Maritza to reflect on her own childhood and how it influenced her parenting style.

“When Christina came, it was very easy to go back to the Costa Rican way [of], ‘Don’t do this. Don’t do that.’ I had to learn very quickly [that] we’re not in Costa Rica anymore. I didn’t go and spend nights at my friend’s house, so it was something that I needed to learn with my daughter. [To] not be afraid to ride your bike and fall. We were so protected by my family.”

One of John and Maritza’s main priorities while raising Christina was creating a bilingual household. Christina, now working as a kindergarten teacher in Urbana, Ill., has used her Spanish skills to further her teaching with some Spanish-speaking students. She appreciates the doors that being bilingual opens.

“It was really great because I got to learn both languages at once,” Christina said. “My mom would speak to me pretty much only in Spanish and then my dad would speak to me in English. My mom would make me respond in Spanish but as I got older, she would talk to me in Spanish [and] I’d respond in English. I always grew up listening to both and then in the summers, we would go to Costa Rica for about a month so I got to practice a lot there as well with my family.”

John is equally appreciative of the benefits of Christina’s bilingual lifestyle, specifically her connection opportunities across countries.

“It’s not a big deal for [Christina] to go to another country and speak Spanish,” John said. “It’s natural for her to do that. And essentially she is part of two different cultures: the culture in the United States and Costa Rica. For her, it’s natural, because that’s what she’s always known.”

As Christina grew up, their family would travel to Costa Rica to visit Maritza’s family once every two years for Christmas. The trips were rich in experience for the whole family, especially Christina, who witnessed lifestyle and cultural differences between the two cultures she’d been raised in.

“I made some friends in the neighborhood,” Christina said. “I would play soccer with them. And it was really a great experience, because even as a little kid, I got to see what a different part of the world is like and what life is like for them. They don’t have air conditioning, for example, and it’s hot there, so that was something I had to learn. Not everyone always has all those conveniences that we have here. Seeing what other people live like was eye opening.”

As Christina grew up, Maritza began to see differences in the level of independence between herself and Christina. She attributes these differences to the way they were raised: Christina with more autonomy than Maritza was able to have.

“I feel like I’m very strong and not afraid of doing things, but my daughter is a very strong woman,” Maritza said. “If she had to travel from Arizona to St. Louis by herself driving her car, she would do it. I don’t feel like I want to do that. I want to have somebody with me driving that long distance. She’s very, very independent. I am independent, but I’m more cautious about things, and I think she’s more [of a] risk taker.”

As Christina grew into an adult, she reflected on her life compared to the life her mother had at her age. She sees their differences, which has motivated her to widen her lens of the world and help where she can.

“[Maritza] always told me about her experiences,” Christina said. “When she was a little girl, she grew up very poor, so they didn’t always have the same things that I had as a kid and she would help me understand that sometimes, that I have some privilege and I’m lucky that I have the things that I have. And that’s why we need to help others that don’t have those things. When we have a lot, it’s good to give back.”

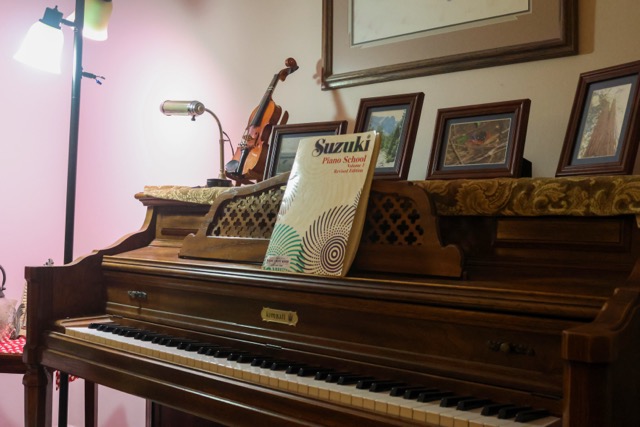

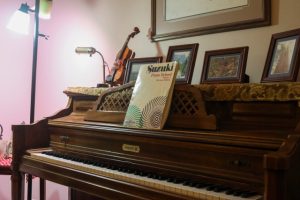

The merging of two diffrent cultures is evident in Maritza and John’s home. Though Maritza may not still hear the same song of Guanacaste each morning, her songs now come from a small speaker on her kitchen counter, playing music from her own, and a variety of other cultures.

“We have had the opportunity to travel a lot, not only in the United States, but in other countries,” Maritza said. “So in our house, you always hear music in different languages. There’s always some Italian, French, Spanish [or] English music [playing]. Same thing with the cuisine. Our house is very diverse when it comes to food. I cook a lot of Costa Rican food and a lot of food from the United States.”

Christina’s preferences have also been broadened by the way she was raised.

“I feel like my taste in music is very wide because I love all the songs I my mom would listen to, all the Spanish radio and the Spanish pop songs, but then I also love my music here in America and my American pop music. And then my dad grew up here in the United States but his family came from Ireland, so [I] even like some Irish folk music. I feel like I have a wide range of music tastes, which is something that I really enjoy having grown up in a bilingual household.”

Going forward, John and Maritza hope Christina will hold onto the richness and tradtion of both cultures she grew up with.

“I hope if [Christina] has children someday, that she would raise them bilingual as well, [and] that she always maintains her contacts with both cultures,” John said. “[I hope] she does go to Costa Rica after we’re gone [and] that she’ll always maintain that contact with her family in Costa Rica. I’m sure she will.”

Through all her travel experience, both within the United States and outside, Maritza has learned about a variety of cultures and people. She never takes it for granted, and encourages others to do the same.

“Have a very open mind about the world,” Maritza said. “You do not understand something until you see it. Once you are there, you learn and you understand. Nobody’s telling you can form your own ideas. That’s one thing that I am very grateful [for]: that I had this opportunity [to see] the world and how people live.”

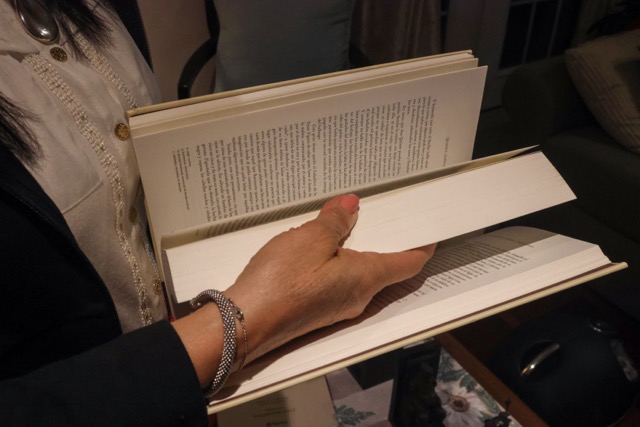

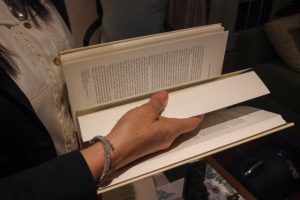

Caption: Maritza works in her office at home, pausing to cut a slice of homemade cake to enjoy with her husband. She loves to teach “Don Quijote de la Mancha,” by Miguel Cervantes, to her students, so student-gifted Don Quijote memorabilia in the form of books and statues populates her house. “When I was learning English, I really liked the process of learning another language and being fluent, so I wanted to do the same with students,” Maritza said.

![School resource officer Rick Ramirez sits in his office. He usually spends little time in his office throughout his day of work, focusing on other issues. “Where our students are, I try to be,” Ramirez said. “Sometimes I get off at 2:45 p.m. when nothing’s going on, or sometimes I get off at 10 p.m. [Those are] my hours.”](https://laduepublications.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Hsiao_20241203_ID_RickRamirez_007-799x1200.jpg)

![Reva poses in front of her home and address plaque. After reuniting with her father and grandparents, she has made many new memories and retained her culture. “We have a lot of Indian cooking going on,” Reva said. “I also like telling people about Indian food, mainly because that’s something that really connects me to [Mumbai].”](https://laduepublications.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/At-Home-1200x799.jpg)