War is often a time of sorrow, violence and loss. Even just hearing the word projects a dim cloud over the mind. War takes and never looks back.

However, for teacher Meg Kaupp, this was the complete opposite. In the time of the Cold War, Germany provided more than just a nice vacation for her. Since her teenage years, through her young adult life and all the way up to her professional career, Germany has been her largest influence. Professions and true love have all stemmed from this country.

“The interest was there my whole life,” Meg said. “I have no idea where that came from. There’s obviously family history, as many Americans have, but I really wanted to be able to read and speak German. I was really intrigued with German history.”

There was no question about where her future led. The decision was final: she had to see Germany.

“I went to Germany when I was 16 for a year to start [American Field Service],” Meg said. “I was there for my junior year of high school and then I did a double major in college and one of those was in German. Then after I graduated from college, I had a Fulbright to Germany for a year, which is a study fellowship.”

Through all the studying and travels, Kaupp discovered another passion — history. After teaching a variety of subjects for 22 years, history was the one that stuck, and eventually brought her back to Germany.

“It’s easier to understand what’s happening in the world today when you understand where we were before,” Meg said. “I like feeling connected to people in places that no longer exist because you see the foundation of what was laid then. To me, there’s a timeless element to it that I really like.”

Her passion for history stemmed from Kaupp being right in the middle of history itself. The Berlin Wall was constructed in the early 1960s and taken down by the German people in 1989, and Kaupp witnesssed it all.

“Back when Germany was divided, there were no Americans,” Meg said. “It was difficult to get to East Germany, so we had host families in the West. They made sure we went to East Germany. In order to get to West Berlin, you had to go through the east border. We took a train and when we got to the border, the soldiers got on for their passport check. We had to have special transit visas in order to travel. They had guns and German shepherds with them, and it was very intimidating.”

While the regulations in the East were strict, that’s not how the city portrayed itself. The rules provided a backbone for the well-being of the country itself.

“I felt it was very safe there,” Meg said. “We would walk into stores and I remember there being children wagons, or like you call them [in German], kindergarten, the strollers. The kids would be in them. The parents would be shopping and they would leave their kids outside in the strollers while they ran into the store to grab something really fast.”

The city was safe, but not because the city was filled with hope, but because every day, citizens lived in fear of unlawful imprisonment. While Berlin was divided, its people were united in the walls’ destruction.

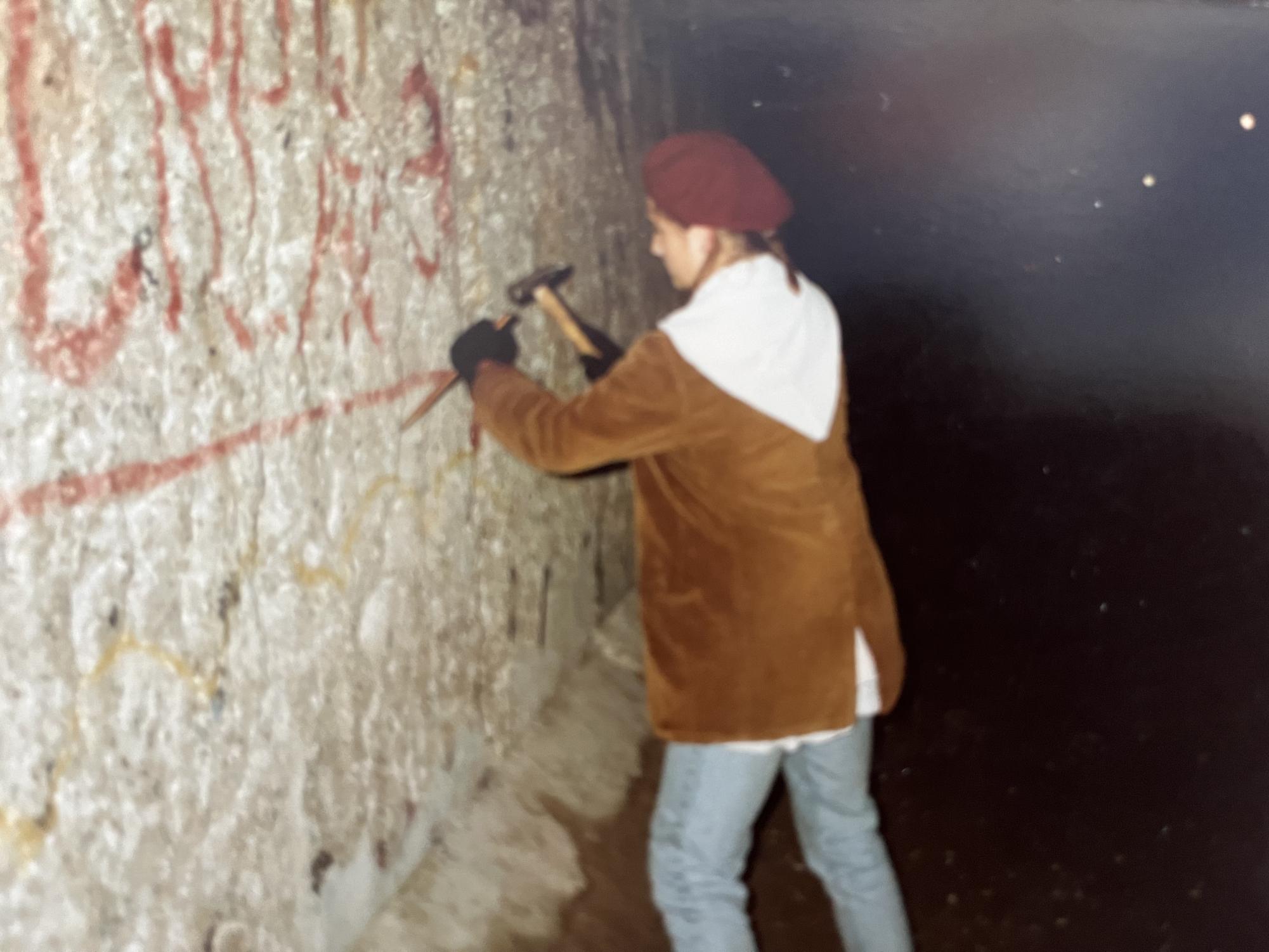

“I remember being in Berlin,” Meg said. “We were there when the wall fell. On the western side you could walk right up to the wall. We took sledge hammers and little chisels. We went in at about 10 o’clock at night and they had these huge floodlights on the Brandenburg Gate there in the heart of Berlin. So we didn’t want to obviously go there. So we went a little bit further down and we’re sitting there just being goofy kids, hammering on the wall, [and] suddenly two guards walked up to us. They were Eastern guards and we freaked out. What you don’t realize about the Berlin Wall is that it was two walls in Berlin. There was this ‘no man’s land’ and they had land mines there.”

Experiences, like being a living part of history, stay with a person for life. The memory of the fall of the Berlin Wall remained with Kaupp, enough to make her want to move back to Germany.

“I think about it all the time, this idea of being in the middle of that, because about five years later I moved back to Germany,” Meg said. “I moved back to the former East and I was one of two Americans in the city.”

While it may appear lonely being only one of two Americans in a city, this exclusivity attracted the eyes of a particular German man: Boris Kaupp, her soon-to-be husband. Meg and Boris came from wildly different backgrounds.

“My hometown is a tiny village with about 300 inhabitants right at the border of the Black Forest; it is very rural,” Boris said. “What I liked as a child is that you were always out in nature. I could leave my parents house, walk 100 yards and be in the woods.”

However, in the 1980s, growing up meant every young man was required to serve his country, Boris included. While he wasn’t there to witness the falling of the Berlin Wall, he still remembers the momentous event of its politically-charged crumbling.

“That was the number one thing on the news every single day for a year or so, but I had never been to the [German Democratic Republic],” Boris said. “I had little idea of how things actually were in the GDR except for some things that you read about. Funnily enough, I remember getting annoyed that there was nothing else on the news. It only struck me years later what a big deal that was.”

Shortly after his service, when schooling began, Boris had a new mission in mind: meeting the love of his life.

“We met in the North East of Germany, which actually is the former GDR, and we were both living in the same city at the time and we were friends for a good while,” Boris said.

They didn’t stop at just friends. Boris quickly took notice of the American newcomer.

“Meg was the only American in that entire city of 50,000 people, so she was quite well known,” Boris said.

They tied the knot a couple years later. After living in Germany for a little while, another big decision was made, coming back to St. Louis and starting a family. However, this family in St. Louis stemmed greater than just their immediate family. A family was started in the teaching space at Ladue. Teacher Riley Keltner shares high praise for Meg.

“It’s always been a really special relationship,” Keltner said. “She is someone who I looked up to from my very first day of student teaching. I always found her to just be so cool. She is just effortlessly cool. She has really been a role model for me and how I want to teach. I’ve always seen her as someone who has very high expectations for her students, but also someone who is always there for her students and knows her students better than anybody. That combination of being able to have great relationships, but also hold your students to a very high standard is something I’ve tried to model my own teaching after.”

Through countless hours of teaching, Kaupp and Keltner have built a friendship that has gone further than just a smile and a wave in the halls.

“We are very close friends,” Keltner said. “We do things outside of school together. “I have the dream one day where she will accompany me to Germany because my family came from there in the 1700s,” Keltner said. “I would love for us to go on that trip together so she could translate for me.”

Through 22 years of living through history, Meg Kaupp has quite the resume, all shaped by the influence of Germany that spurred her passion for history.

“I like to think that human beings play a bigger role in shaping history than we sometimes realize,” Kaupp said.

![School resource officer Rick Ramirez sits in his office. He usually spends little time in his office throughout his day of work, focusing on other issues. “Where our students are, I try to be,” Ramirez said. “Sometimes I get off at 2:45 p.m. when nothing’s going on, or sometimes I get off at 10 p.m. [Those are] my hours.”](https://laduepublications.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Hsiao_20241203_ID_RickRamirez_007-799x1200.jpg)

![Reva poses in front of her home and address plaque. After reuniting with her father and grandparents, she has made many new memories and retained her culture. “We have a lot of Indian cooking going on,” Reva said. “I also like telling people about Indian food, mainly because that’s something that really connects me to [Mumbai].”](https://laduepublications.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/At-Home-1200x799.jpg)