In arenas across the country, crowds rally: the air is heavy with heat and breath, the warmth of bodies close together with anticipation. The skyline is crowded with pickets and signs, while phone flashlights turn the light-polluted sky into a sea of stars, and this, here and now, with these voices pressing one great roar to a feverish pitch — this is where the difference is made. Their voices say, “This is history in the making.”

Two miles down the street, a local candidate knocks on doors. Most of them remain closed, but in their mind, every opened door is a spark of hope. Next door, a teenager rants in a group chat with friends about the broken nature of the system, flickering between screenshots of video games and shared biology notes.

The heart of politics is this — change. On both the national and local level, government is often seen as the only way to make change in the world, whether through voting or other forms of civic engagement, like campaigning with a candidate. In the midst of a national election, others have begun to move away from the beaten path, believing that true progress can only come from working outside the system, or rebuilding it from the ground up. Now, more than ever, the influence of politics is front and center, raising a crucial question: Does the system work — and, if not, how do we fix it?

Problems in Politics

Despite our government’s influence on both the local and national level, this system is far from immune to problems. Many groups of people from a number of different ideologies have found their own gripes with the system we live in.

“It’s harder and harder for voters that want to stay informed to find coverage of things that are happening locally,” Missouri State Senator Tracy McCreery said. “Throughout the years, a lot of the trusted, well established newspapers and radio stations have suffered some tough times financially, and have ended up cutting reporters, cutting staff, people [and] cutting team members.”

According to Pew Research Center, 17% of Americans between the ages of 30 to 49 often receive local political news from their local news station. Young people are especially vulnerable to this lack of local coverage: the same study found that only 12% of people aged 18 to 29 often received local political news.

“An average high school student is probably not super involved in politics, especially because 9th through 11th graders can’t vote,” Georgia Bland (12) said. “Even seniors who can vote aren’t super educated or feel that it doesn’t really affect them and they don’t really know what they’re voting for, so sometimes they just choose not to vote. I think that a lot of the issue is [a] lack of education and [a] lack of knowledge that you do have an important role in the vote and every vote counts. If everyone said their vote didn’t count, they’d have no votes.”

Generation Z has been found to hold a lower level of trust compared to other generations. This may factor into why they seem to be less politically engaged. A survey conducted by The Public Religion Research Institution found that only 41% of Gen Z holds a great deal or some amount of trust within our governmental system, compared to 51% in Generation X and 56% in baby boomers.

“They’re selling politics to you as a spectacle,” Jacob Barnes (12) said. “You’re buying opposition. You’re buying entertainment. Politics right now is based on consumption.”

Part of the issue with a focus on consumption also means that media coverage centers on what draws in revenue.

“You hear more about [national politics] because you follow where the money is,” social studies teacher Mike Hill said. “Political action committees and super [political action committees] that draw lots of money from different groups that keep national races in the forefront of media attention.”

This focus on those in power also reflects an inherent source of flaws with how policy is made and written in a representative government.

“Government is not necessarily inherently corrupt, but the way [ours] currently runs has a lot of corruption in it,” Calvino Hammerman (10) said. “It’s a lot of rubbing shoulders. People go places to make deals. Are all these deals made by the most upstanding citizens? No, but that’s where real governing happens.”

Not only are flaws being examined within our current system, but some youth are looking more broadly and are observing larger issues within our government. This thought process can lead some down the road of thinking that brings up the question: Are there flaws within our system? Or is this system fundamentally flawed?

“The way that politics is [discussed] is especially dangerous when it comes to this huge emphasis on [how] the only way to get stuff done is through your elected representatives,” Franklyn Yang (12) said. “I think that that’s not true, because a lot of our elected representatives don’t represent our issues, and a lot of them are paid, and a lot of them are just pandering to people.”

In contrast, other students find the system to be something you have to work within, viewing representatives as the best way to create change.

“Getting the people who share your views elected is what can help,” Hammerman said. “What students can do is to find [their] congress person running in [their] district or [their] senator running in [their] state. Find which one of them shares [their] views and help them be elected.”

In other instances, part of the difficulty of interacting with complex issues and looking for solutions is the loss of nuance.

“[For example], when you think about the way we talk about poverty it’s like this: ‘If we just give more foreign aid to Africa, they can develop the same way that we did,’ as if American companies don’t rely on extracting cheap labor from very impoverished countries around the world, as if that’s not the basis of all of the wealth that the global north has,” Yang said. “I think a lot of the political rhetoric that Gen Z engages in is still vulnerable to contributing to rather than dismantling hegemonic ideas.”

Engagement

While much of the rhetoric surrounding young people in politics right now is that of a lack of involvement, some believe otherwise.

“I’m always impressed by the amount of awareness that my students exhibit in the classroom,” Hill said. “They’re not just exposed to lots of streams of information, but they pay attention to them. They actually read them. That’s one of those things that older generations look at and quickly dismiss. People of a certain age believe that [young people] don’t keep up, that all they do is [look at] their phones. To those people, I always say, ‘Have you seen TikTok?’ It’s a learning channel. It really is. I’m always blown away by the amount of awareness that students bring.”

Though social media can be a helpful resource for absorbing information, making tangible change and engaging with politicians directly through social media can be a struggle as a result of the sheer quantity of information and data that exists online.

“I think people do care about many political issues,” Hammerman said. “But where I personally see a lot of people directing their energy is into their Instagram posts and that is meaningless. Our legislators, even the ones that disagree with you, care about your opinion, but they are not looking at your social media page. If you want them to hear your opinion, you have to go to them and tell them.”

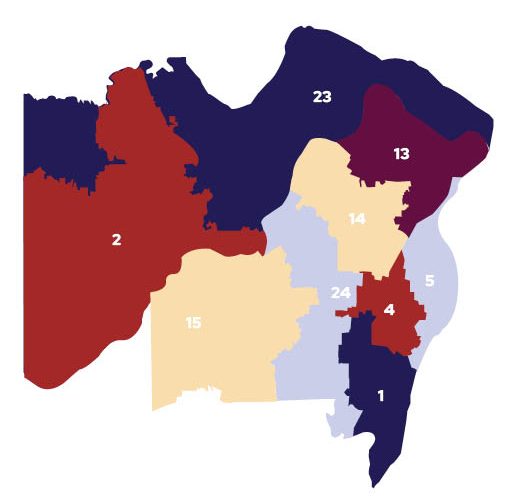

Local legislators, in particular, are easily accessible by their constituents, whether through community events or online contacts, but often that accessibility isn’t taken advantage of by citizens. According to Missouri’s 2022 Voter Turnout Report, which reports based on the highest turnout for a race or issue in each county, no turnout rate surpassed 60%. The county with the highest turnout, Worth, Missouri, counted 59.1%. Worth was also the smallest county, with only 1410 registered voters.

“If you live in a municipality like Ladue, elected city council people handle trash pickup, snow plowing, taking care of the parks, [and] that’s all very, very critically important,” Ladue Mayor Nancy Spewak said. “Those are all people that are [locally elected] in April every other year, and those elections have very low turnout. When you think about the things that really can impact your day to day quality of life, very few voters are even picking those folks.”

Low voter turnout is an issue because voting is often seen as the most effective way for citizen’s voices to be heard in modern democratic institutions, even amidst fears that individual votes are insubstantial.

“The avenue that you are given to change is through the vote,” Hill said. “Whether you think that matters is inconsequential. If you don’t vote, then you shut off any and all possibilities for your vote to make any kind of salient change. If you’re really that concerned about what’s going on around you, you will participate.”

To others, though, honing in on voting as the only avenue of change allows governments and politicians to dictate what changes are even on the table, restricting the scope of what political movements can do in government.

“They didn’t vote the abolitionist movement into existence,” Yang said. “They didn’t vote the gay rights movement into existence. Those movements existed first and then pressured politicians into doing things and pressured government into doing things. It was because there were people on the ground disrupting civil society and grinding it to a halt and forcing government to do something. That’s the kind of politics that’s probably most effective at creating real change.”

Amidst these debates on the power of the vote and the system, while Americans grapple with finding the most significant way to make change, the presence of politics in the lives of democratic citizens is ultimately immutable.

“Whether you’re interested in politics or not, politics is interested in you,” McCreery said. “These politicians are going to do things that impact your life, and ideally we want that impact to be positive. We really don’t have an option right now as Americans to disengage from things, because there are decisions happening in the legislative branch, in the judicial branch, that are impacting all of us. It’s part of our obligation as Missourians and as Americans to find a way to be engaged.”

Reform

It is nearly universally acknowledged that politics exists, but the question still remains on whether it can be boiled down to a matter of voting on candidates, policy and bureaucracy, or whether it encompasses broader social and cultural movements. Many agree that the current bureaucracy requires change, but there are obstacles in achieving this.

“What history has taught us is that systems are systemically opposed to change,” St. Louis County Prosecutor Wesley Bell said. “It’s not just the policies, it’s the entities and the stakeholders who have made careers off of these policies.”

This raises the dilemma: if the system itself is resistant to change, is reform from within enough to address issues relating to self-interest?

“The political rhetoric that we employ has obviously been made to sustain the world we live in,” Yang said. “It’s all reactionary. People never say it’s a problem with the system. [They say ] it’s always a problem that needs to be fixed within the system; it’s not a fundamental flaw, it’s just a temporary issue.”

Frustration with the effectiveness of government is becoming increasingly common. 58% of Americans are not satisfied with the way democracy is working out according to a 2021 poll from the Pew Research center. Yet, for many, the idea of radically rethinking or dismantling the entire system is more idealistic than realistic.

“The system of government is not going anywhere,” Bell said. “Some folks will say, ‘We need to just tear it down, start over.’ Okay, that sounds great, but it’s not happening. One of my favorite sayings is, ‘If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu.’ Decisions are going to be made, and if you choose not to be part of them, those decisions will be made for you.”

However, some believe that by focusing solely on how to navigate within the current framework, discussions about deeper changes or alternative systems that may be of greater benefit can be prematurely dismissed.

“We’re degrading thinking in the first place by saying these words are scary, or the word socialism is scary,” Barnes said. “People throw away the option to even talk or think about [alternatives] because it’s too hard. Civics classes are good, but [they] don’t really teach you how to think outside the box. To think outside everything that’s built you up. We need to think about the confines of what we talk about and what we view as realistic and whether [that’s] defined by us as people or just prescribed to us by prior thinking.”

According to others, another issue that lies within working only inside of the system stems from hyper-focused ideas of where progress comes from, as well as the tendency to off-load the burden of creating solutions onto the private sector.

“The end of our political horizons is just more technology, more innovation,” Yang said. “It all falls within these barriers which we’ve constructed around ourselves, which is that we always must maximize productivity, maximize efficiency, or else the whole system crumbles apart. Technology should serve people, not people serving technology. [The current] rhetoric about the climate, where we should let the scientists solve it, is a symptom of that broader ideology. It’s something that’s been programmed into our societal values to uphold the society that we have.”

The responsibility of not only shifting and expanding one’s thinking but also reworking politics and finding ways outside of government to seek change is a gargantuan task, and not something within the purview of the individual.

“Try not to get overwhelmed,” McCreery said. “Things are overwhelming. Just try to focus on helping a family member, helping a neighbor, helping a friend and making a positive difference every day in the life of one person. I think that’s a way to kind of put one foot in front of the other.”

In this more personal approach, there can still exist an opportunity for broader change. Movements, whether radical or moderate in their approach to reform, most often start with just a couple of people.

“I think people just need to talk more about these things,” Barnes said. “That’s the only way our political horizons will ever expand. I think it really is an actual protest to care. The system inherently wants you to be cynical and act as if it’s just the way it is and it’s the only option and you can’t do anything about it. [Even] just thinking about this stuff, talking about it, that’s caring.”

![A client poses for a photo. Although Hannah Hiken (12) enjoys painting nails for others, she prefers to have control of her own artistic freedom. “I do [nails] on myself a lot. I think that's what I really enjoy most,” Hiken said. “Doing it on myself, because I can choose everything I want to do.”

Photo courtesy of Hannah Hiken](https://laduepublications.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/IMG_1740-1200x986.jpeg)

![Duckham spends large amounts of her free time reading. Dealing with fewer classes this year, Duckham’s bookshelf at home has seen more use. “I call every book my favorite, but not truly every book [is]. I wrote my dissertation on Herman Melville, so I guess I'd have to say Moby Dick, is definitely one of my all time favorites,” Duckham said. “I really do love both British and American novelists of the 19th century. I tend to prefer nonfiction over fiction. For some reason, I think there's so many great non fiction writers, and I love the whole idea of something being true.

(Photo Courtesy of Janet Duckham)](https://laduepublications.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/IMG_6605-1200x900.jpeg)

![ABOVE: Duncan Kitchen (10) plucks the strings of his guitar at his home. Duncan’s older brother inspired him to start playing the guitar two years ago. “On any given day [in Alaska], you could walk up the mountain start a campfire [and] play guitar,” Duncan said. (Photos by Vincent Hsiao)](https://laduepublications.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Hsiao_20250325_DuncanKitchen_010-1200x839.jpg)