Allen You is a senior at Ladue and the co-editor-in-chief for the Panorama. This is his second year on the staff. His guilty pleasure is listening to too...

December 16, 2021

I hate the suburbs, part 1.

Back in September I started Allen Hates Politics partly on a whim, partly seriously. I wrote because I just kind of felt like it, but also in hopes that Allen Hates Politics would develop a small, loyal readership that would stimulate conversation at Ladue. Politics is often seen as boring or too polarizing to confront and I wanted to change that notion little by little. Politics, in my view, is actually incredibly interesting as well as unfathomably impactful. At the least, I wanted just one person to read the columns and ignite their own hate and passion for politics.

At the moment, I’m not exactly sure of the readership of this column. So, if you have been reading Allen Hates Politics, firstly, thank you so much. It really makes me happy that you’ve been enjoying the column. And second, please reach out! I’d love to hear your feedback and thoughts on the essays so far.

As for the Allen Hates Politics SEASON ONE FINALE SERIES (!!!!), I need to vent with you all. I’ve had a lot on my mind lately and I need to get it out.

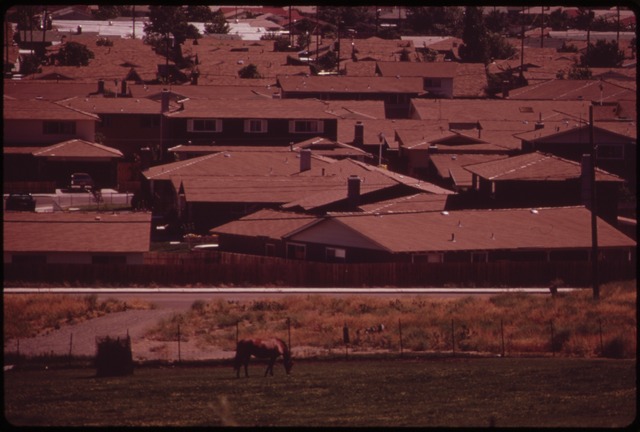

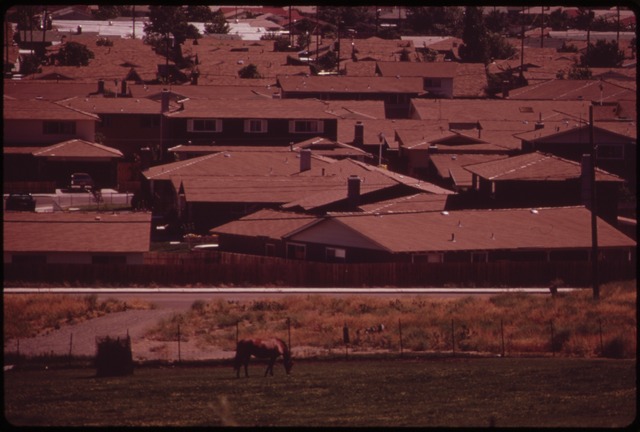

Ladue is ugly. I mean, not as ugly as Chesterfield. At least we have trees. But still, Ladue is kind of an eyesore.

For one, why are the front lawns so big? I get having a big backyard, but what are we doing in our front lawn? Watering it? And then mowing it? Walking across it to get to our mailbox? It is such wasted space. Some lawns are so big you could legitimately build a commercial center in it. But no, we need mind-numbing amounts of Poa pratensis for…aesthetic purposes…?

And houses. Oh my god, the houses. Sometimes I look at my own house and think, “This is just a box with a triangular roof.” Then, I look at my neighbor’s house and I have the same thought. And then I go to my friend’s house and it’s the same. It’s all the same: rectangular prism with a nice triangle (or combination of triangles, woah) on top and in front, a rather painful excuse for a design choice that we call the front facade. Or as one writer puts it, a “neurotic potpourri of superficial ornamentation.”

I feel like I could pay less attention to the repetitive ugliness if, you know, anything happened. But the only movement I can detect in Ladue neighborhoods are cars whizzing past, leaves fumbling around like desert tumbleweed and occasionally a squirrel. Human life is cooped up in their respective rectangular prism. This suburban life of mine is so unbelievably sterile that I’m going a bit insane. I feel like I need some kind of new stimulus otherwise my brain will start to smoothen.

Venting over. Let’s get into the politics of this thing.

If ugliness was the only downside of the American suburb, I’d be content with life. After all, babies are ugly, yet I still like them. But babies aren’t responsible for opportunistic inequalities, unsustainable development or several housing crises. Ladue, like any other suburb, fits this sinister description far better.

Green Day did it first (this is a joke) but I’ll pick up where they left off. The suburbs suck. And it’s politics (again) that’s at fault for this dumpster fire that I happen to live in.

So firstly, what makes a suburb a suburb? Last time, we talked a little about the businesses that arose from suburban policy and more specifically, the Interstate Highway System (brand fast food, retail supermarkets and shopping malls). These institutions are in wide abundance in the zip codes some of us call home. I live two miles from Plaza Frontenac, which used to be next to a Panera (not really fast food, but you get the point), which is across the street from a Schnucks. And while those are certainly key features of suburban life, they were more a byproduct rather than a cause of suburbanization.

More to the point, suburbs are just communities bordering a city. Many suburbanites enter the city for work and live in single-family homes. I’m a prime example of this. My father travels into the city to work at Washington University of St. Louis and we live in a single-family home with an excessively large front lawn! Paradise, isn’t it?

Taking a closer look (or for some of you, taking a look outside) would tell you a lot more about suburbs than you’d think. Everything you see is evidence of some kind of policy. The layout, the housing, the streets, the greenery were all intentional. And that’s the primary focus of this series: suburbs didn’t just spawn, they were politicked into existence.

Like the Interstate Highway System, suburbanization as we know it began right after World War II. Veterans, relieved of duty, returned to the U.S. to find themselves in the midst of a housing shortage. Urban homes became crowded as veterans found refuge with their relatives, friends and even strangers. Cities were under crisis as they 1) tried to accommodate the many returning veterans and 2) tried to transition back to a peacetime economy from the wartime economy. To deal with this conundrum, the federal government made a sweeping (and maybe correct?) decision.

Disclaimer before this section: I don’t know much about buying homes.

Right before the end of the war, Americans had been living on wartime rations for over three years. That means that each American was not allowed to buy more than a specified amount of certain products (rubber, sugar, milk, etc.). Since Americans weren’t spending money, their savings started to stack up. It’s like when you squeeze a hose while the water is still running: the water builds up at the choke point and when you release it, a massive amount of water shoots out. Same case here: when the war ended, Americans needed something to shoot their money at. Namely, cars and houses. By the end of the 50s, 75 percent of households owned a car and home ownership had skyrocketed.

But it wasn’t like they each had 20 grand to splurge on whatever. In fact, it was the government that made it way easier to buy and lend. There are two primary policies that accomplished this: the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (a.k.a. The “GI Bill”) and the Federal Housing Agency’s (FHA) regulation of mortgage lending.

For this, we need to go back in time again to the 1929 home foreclosure crisis that led to a housing market crash that coincided with a stock market crash which also just happened to be the cause of the Great Depression. Stuff sucked for a long while until this guy named Franklin Delano Roosevelt came up with this zany idea called the New Deal.

With Roosevelt’s New Deal came the National Housing Act that included the creation of the FHA. The FHA switched the common 6-7 year, 50-60 percent down payment mortgage (that sucked) and started to offer FHA-insured “standard fixed-rate mortgage (FRM) contracts with longer maturities (20-30 years) and a higher loan-to-value ratio (80 percent and above),” according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

This was a lot nicer for several reasons. First of all, you didn’t need to have a ton of savings to purchase a house (down payment was 20 percent as compared to the previous 50-60). And the longer mortgage periods allowed for homeowners to build up equity on their homes. The federal mortgage standard wasn’t widely adopted for a while, so the implementation was slow. But by the time the war ended, these safer and easier mortgages were offered widely to prospective homeowners. And as discussed before, they had the money to make these down payments.

So at the end of it all, mortgages were revolutionized and right in time for a postwar housing boom. Construction companies and builders needed space to expand, and why not build in the outskirts of cities where highways were already being built to access cities and land (and potential development) was in large abundance? Suburbs* were in the right place at the right time for this massive housing expansion and everything sprouted from there.

“By the 1950s, as many as one-third of home buyers in the United States received support from the FHA and VA programs, and home ownership rates rose from four in ten U.S. households in 1940 to more than six in ten by the 1960s. The vast majority of these new homes were in the suburbs,” according to one study.

(*Note: pre-war suburbs did exist, I’m just too lazy to commit a section to talking about them. They were very different from the modern suburb and known as streetcar suburbs. As suggested by the name, they centered around streetcar lines instead of highways and automobiles. They still exist and they’re actually kind of nice.)

Even by today’s standards, this is perfectly sound economic policymaking. Roosevelt accomplished exactly what was needed of him. He got the housing market out of a slump with deficit spending and the standardization of less risky mortgages. And when Truman picked up where Roosevelt left off, he brought this policy to the extreme, stimulating a vast postwar housing boom. You could access these tremendous new offers for brilliantly peaceful suburban houses, get out of the city, out of the rubble and live out your dream!

You know, if you’re white.

White Flight

The infamous 1944 GI Bill. I said before that this was all perfectly sound policymaking. And it is… it just wasn’t enforced correctly. This postwar housing boom was strictly “Whites Only,” excluding black people from ever having the same opportunity to move away from the city and buy a home.

Arguably the biggest provision in the GI Bill was that veterans could get mortgages for little to no down payment, allowing veterans to walk into a home basically for free and finding the money to pay their loans off later. It makes perfect sense, since veterans had been fighting a world war instead of earning income for the past half decade. And it worked beautifully, the “effect of the VA’s zero downpayment policy accounts for approximately 10 percent increase in home ownership,” according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

But essentially none of it went to black veterans, locking them out of any upward economic mobility.

And apart from just the housing provisions in the GI Bill, there’s a laundry list of ways in which white-owned businesses and institutions squashed black people, especially veterans, from claiming any of the government benefits they were supposed to be afforded.

Erin Blackmore puts it best: “The original GI Bill ended in July 1956. By that time, nearly 8 million World War II veterans had received education or training, and 4.3 million home loans worth $33 billion had been handed out. But most Black veterans had been left behind. As employment, college attendance and wealth surged for whites, disparities with their Black counterparts not only continued, but widened. There was, writes [Ira] Katznelson, ‘no greater instrument for widening an already huge racial gap in postwar America than the GI Bill.’”

From the end of the war to the 1970s, this was the story of American suburbanization. Sound economic policymaking corrupted by the Jim Crow Era’s racism made the suburbs what the suburbs are today. Investment in white suburbs came with the disinvestment of racially diverse urban centers. And that’s still prevalent today. The racist housing trends that afflicted the 40s through 70s never left us, they’ve just changed form. But that’s a story for another time.

Suburbs didn’t just spawn. They were politicked into existence to solidify racial disparities. And you may ask, “Wait, aren’t you a racial minority living in a suburb?”

In conclusion, I hate politics.

Allen You is a senior at Ladue and the co-editor-in-chief for the Panorama. This is his second year on the staff. His guilty pleasure is listening to too...